This article was originally published in French on David Fayon’s website.

The metaverse has been getting a lot of press coverage since the Facebook company changed its name to Meta a year ago. While nascent solutions were already available, such as Second Life, a 3D virtual world launched in 2005 when the term Web 2.0 appeared, virtual reality headsets, NFTs, blockchain technology, and faster internet speeds have reignited interest in the metaverse. But between fantasies, a new eldorado for brands and reality, what is the truth of the meta?

Metaverse and Positioning in the Web3 Era

For the past several months, the term ‘metaverse’ has been trendy. Metaverse, from the words ‘meta’ (going beyond, transcending) and ‘universe’, is a virtual 3D universe in which a person can interact with other people generally represented by avatars. These can be virtual and persistent worlds connected to the Internet via augmented reality. The term was even voted tech buzzword of the year in 2021.

Just as many companies talk about digital transformation without truly implementing it, but rather to garner media attention, it is important to know what we are actually talking about, because since the triggering event on 28 October 2021 when the Facebook company announced its rebrand and its name change to Meta, over-expectations have emerged. Since then, there seems to be confusion, with existing digital services rebranded and taken into account in the metaverse as if revenue figures were added together several times over without deduplication. Otherwise, how could a firm such as McKinsey, which attracted criticism for its healthcare recommendations, predict that the metaverse has the potential to generate five trillion dollars in value by 2030, a figure roughly equivalent to the GDP of Japan, the world’s third largest economy behind the United States and China? Other firms, such as Gartner, Deloitte, Accenture and BCG, have also produced studies with figures showing that the metaverse has enormous potential. These are merely projections and models struggle to anticipate shifts over an eight-year period such as this.

Observe also that internal investments by players in the metaverse space – around 20 billion dollars – are lower than those of venture capitalists which total close to 100 billion dollars.

The metaverse should be considered from the viewpoint of tech companies wanting to sell their products, and from that of end-user companies (including major brands and the luxury sector) which could have other growth drivers or wish to avoid “missing the boat” if their competitors get in first. For companies, coming in too late could mean losing market share. This is why ongoing experiments are often in proof-of-concept form or based on trial and error without necessarily building a sustainable, solid and profitable business model.

While persistent, multi-user worlds that even have their own currency (such as Linden dollars in Second Life) have existed since Web 2.0 in the mid 2000s, the novelty resides more in the combination with other elements, such as the development of NFTs (which facilitate ownership of virtual digital assets) associated with blockchain technology, whereas virtual reality and augmented reality are of greater interest now that the equipment is more advanced (virtual reality headsets such as the Meta Quest, resulting from Facebook’s acquisition of Oculus in 2014, and haptic gloves, which reproduce the sense of touch). The concepts already exist; the question is how to use them to create useful rather than futile value. It is worth noting that Bitcoin did not need the metaverse in order to develop.

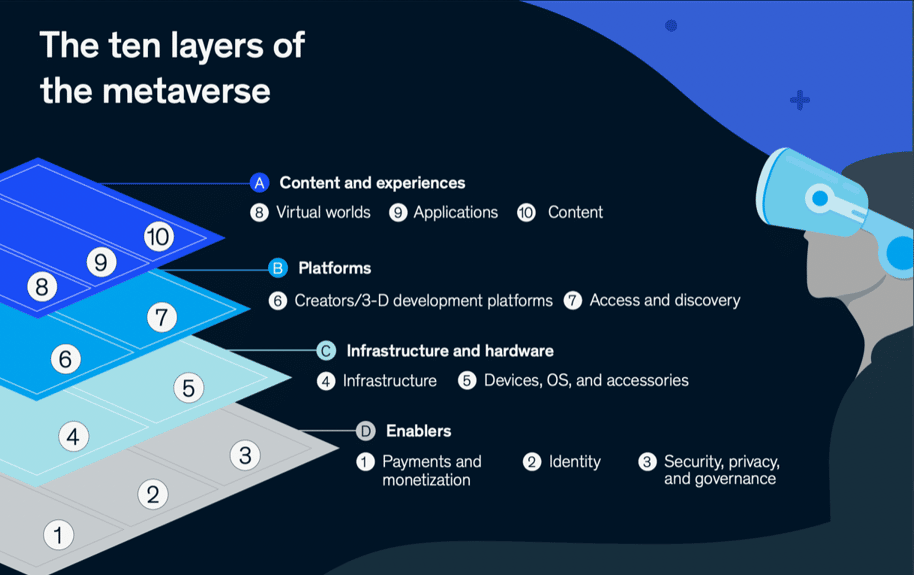

A multi-layered metaverse system has even been modelled, with four, seven, and even ten layers (picture below).

We are currently in the Web 3.0 stage, where the Internet of Things (IoT) and the Semantic Web converge, as I defined it in my book, Web 2.0 et au-delà (Web 2.0 and Beyond). It follows the Web 2.0 stage, which saw the convergence of technical advances (content syndication, style sheets, etc.), a collaborative web where users are actors and interact by producing content, and a new relationship to data, with platforms appropriating often it through the provision of a seemingly free service.

The definition of Web3, the extension of Web 3.0, integrates certain aspects resulting from blockchain technology (smart contracts, NFTs, cryptocurrencies) and, as a consequence, we shift from a centralised model to a distributed model. This is illustrated in the last column of Frederic Cavazza’s diagram (below).

| Web | Web 2.0 | Web3 | |

| Types of businesses | Start-up | Scale-up | DAO |

| Types of applications | Applications to download | Web-based applications | Decentralised applications (DApps) |

| Monetisation | Licence purchase | Pay-as-you-go (PAYG) | Tokenisation/NFT |

| Databases | MySQL | NoSQL | Blockchain |

| Merchant models | Online store | Marketplace | DTC |

| Channels | Portals | Social media | micro media |

| Audience | Visitors | Subscribers | Donors |

| Authors | Publishers | Influencers | Creators |

| Ads | Banners | Native ads | Collaborations |

| Digital identity | Personal website | Social profile | Avatar |

| Messaging apps | ICQ | Discord | |

| 3D immersion | Virtual worlds | Virtual reality | Metaverse |

| Work spaces | Email/Intranet | Remote collaboration tools | Digital workplace |

Recently, Franck Confino published a provocatively titled post about the metaverse that is well worth a read.

Between the metaverse enthusiasts and the sceptics there is a middle ground even though the metaverse bubble might burst. The fact that the dot-com bubble burst in March 2000 and there was no real bubble for Web 2.0 does not mean there will not be one with the Web3 that lies ahead.

One might even wonder if we are not at the beginning of a metaverse decline due to the surrounding over-expectations.

The resulting questions are primarily:

- For what uses that could not be possible in real life? And with what added value?

- Will the tools be accepted for heavy use? (6 hours or more per day and by whom?)

- Will these metaversal worlds be respectful of the environment with all the sensors and data produced and with the use of ethical blockchains more reliant on proof of stake than on proof of work? Energy consumption could skyrocket with the 3D virtual representations of the physical world as well as the numerous interactions and the ensuing proliferation of data and content.

- What will be the potential standards of virtual reality? Because we will have closed worlds and gateways between virtual worlds and from virtual worlds to the physical world and vice versa, along with portability of the data and products created in the metaverse.

- Which laws should apply in the metaverse and how can states regulate a decentralised ecosystem?

In addition, it seems crucial to reconcile metaverse and low-cost technologies so as not to create energy hogs.

Total or Partial Acceptance of the Metaverse and Possible Uses

A recent study compared performing work tasks in the traditional way and in the metaverse (Michael Crider, PCworld), with interesting findings.

The test subjects for the study “reported a 35% increase in work task load, 42% more frustration, 11% more anxiety, and a whopping 48% increase in eye strain. Participants rated their own productivity at 16% lower and their well-being at 20% lower.” Note that between the work configuration in virtual reality offered by the market today and in a few years’ time, ergonomic advances will be crucial to facilitating its acceptance. In particular, glasses are more comfortable than a headset, and information can be added to car dashboards, something which is still in the very early stages right now. Projecting reality onto the virtual environment augments the virtual so as not to isolate the person wearing the headset or some other piece of equipment that remains a constraint. We are not slaves to the tool.

Not everyone is capable of spending 8 hours wearing a virtual reality headset or some other type of specialised equipment. It would appear that virtual reality is more suited to certain specific tasks and for part of the day, with users eventually switching back from metaverse mode to real-life mode depending on the tasks and actions to accomplish. It is likely that a balance will eventually be struck, just as it was for COVID-induced remote working since 100% teleworking is not viable. Human beings are social animals who need to see their colleagues and interact with others or risk sinking into depression. Controlled use of the metaverse would be preferable, although addictive behaviours will also exist, just as they do with video games. From a societal point of view, there is also the risk of creating a digital divide between two categories of citizens: the ‘gilets jaunes’ (“Yellow vest” protestors) with legitimate demands and people in contact virtually in the form of avatars.

A recent metaverse-focused study conducted by the French market research and opinion polling firm Ifop with Talan confirms that the technology is still little-understood by the general public in France. Of the 35% of respondents who reported understanding what it is, 14% said they understood “precisely”. There is a logical difference between generations (42% of 18- to 24-year-olds know what it is, versus 28% of the 65+ age group) and between socioeconomic categories (59% of university graduates versus 27% of people with no higher education). These same two divides – generational and social – can be found in the representations associated with the metaverse and its uses. Finally, 75% of respondent expressed fears surrounding the metaverse, including among 18- to 24-year-olds (49%).

With the metaverse comes a shift from the status of digital consumer via smartphones, computers and tablets, to that of actor in a 3D virtual world interacting with elements like the headset. The goal is to be able to play, interact, consume (by reaching customers in a different way) or work differently. It is about so much more than games, leisure activities (concerts with a VR headset), sports coaching, virtual or augmented reality, and avatars.

With parallel worlds whose design can sometimes be confused with reality, exchanges between avatars and holograms of ourselves will be possible, sometimes with humans and sometimes with automatons, without necessarily being able to distinguish with artificial intelligence – if the Turing test is performed – whether the interaction is human-to-machine or human-to-human. In a sanitised metaversal world, interaction with reality could even become a leisure activity!

Besides the gaming world, one can image a host of uses (immersive training; the cultural sphere; the monetisation of virtual products in the luxury and arts sectors, using NFTs in particular; visiting and decorating a future house before buying it) with gateways between the virtual and physical worlds, enabling someone, for example, to buy something in the metaverse and have their purchase delivered to their actual home or another physical location.

The question is to figure out whether the value of potential uses by the general public is grossly overestimated, whereas the targeted and occasional use of operations in the metaverse by the automotive, aerospace, construction and telehealth industries might create more value. One example might be performing a remote intervention in a hostile environment via the metaverse to repair a defective part. Virtual reality is also used as a therapeutic tool to treat phobias, anxiety, and even addictions. Digital twins will make it possible to duplicate an employee in the physical world, to create their double in the metaverse. Among other use cases, a digital twin can be used to highlight repairs to carry out on an electrical grid, or any other type of remote maintenance.

Overall, in B2B we could have niche markets with a rather big impact, and in B2C a large number of users with a small impact and the risk of this impact becoming “gadgetised”. In such a context, Meta would be compelled to pivot several times with, intuitively, possible Cambridge Analytica type scandals but worse.

The Players, from the Gaming World to Microsoft, Meta and the Others…

The media are focusing attention on Meta, which plans to inject 10 billion dollars by 2030 with its sights set on a mainstream tool using a standard Oculus Quest headset and its future iterations. But let us not forget Microsoft, which has a foot in the gaming world since the Xbox, and in virtual reality with the HoloLens headset. The Redmond-based firm has also created the Metaverse Standards Forum to bring together industry stakeholders. And last January, it announced the spectacular acquisition of Blizzard Entertainment for 68.7 billion dollars (although the situation is not quite clear right now, since the UK’s competition watchdog opened an investigation).

We can also mention the games Roblox and Fortnite, The SandBox for game creation, but also the ambitious Taiwanese company HTC Vive, founded in 2016, Nvidia, etc., not to mention the projects from Apple, which has not yet launched a virtual reality headset but could end up guiding the market, as it did the smartphone market with the iPhone, although the Apple Watch has turned out to be somewhat of a flop. We have an entire ecosystem, both on the hardware side with headsets and haptic gloves, and on the software side with open source multi-platform, multi-user applications such as OpenSimulator or Unity 3D for creating a decentralised virtual world, but also with cryptocurrency portfolio management platforms such as Binance or Coinbase.

It is possible that Meta’s strategy of putting “all their eggs in one basket” is a bad one. Of all the Big Five tech giants (GAFAM or MAAAM), Meta remains the most vulnerable.

Not only did Meta’s COO and number two executive, Sheryl Sandberg, leave the company on 1 June 2022, but Vivek Sharma, the VP of Horizon who had joined Facebook in 2016 and ran the Horizon Worlds project, the first version of the Menlo Park firm’s metaverse, has also stepped down. It is worth asking ourselves whether a universal Facebook-style tool, which is what Meta wants, is appropriate or even ethical, considering the immersion in our lives. It also wants to understand what our brain wants, and that is not necessarily for the best.

Meta official line on this is presented on the page “The metaverse may be virtual, but the impact will be real”: “We are building incredible things for the metaverse. We believe the metaverse will connect people to new experiences. From immersive education and training to new possibilities in healthcare and the workplace, and much more, we are excited about the positive benefits the metaverse will bring.” The page goes on to add, “Possibilities in the metaverse: The metaverse will help take learning and discovery to a new level. People will be able to learn by doing and not just passively absorbing information, diving into new topics and experiences and deepening their knowledge through 3D immersion.”

Finally, I consider that the more intangible and even virtual a service is, the higher the share of added value can be and consequently the higher the taxes, also. In the Middle Ages, a 10% tax was charged, known as a tithe. With the App Store, there is now a triple-tithe (30%) on any apps distributed. With Meta, it has been announced at 50%.

On the French side we have Dassault Systèmes, which has been at the forefront in 3D since it created its CATIA (Computer-Aided Three-dimensional Interactive Application) tool in the early 1980s. They could be a heavyweight in the metaverse on the software side. And as for hardware, to date Lynx is probably the only company to design mixed reality (virtual + augmented) headsets, even though they are assembled in Taiwan, which is on the cutting edge of more than just semiconductors.