With the recent buzz surrounding generative artificial intelligence — i.e. AI that is able to produce text, images, sound and more — since the launch of ChatGPT1 and image creation tools such as DALL-E and Midjourney, it has been impossible to escape this tsunami which is likely to disrupt a whole range of human activities for blue-collar workers, but also for white-collar workers who had so far been spared from automation and robotics. The questions that arise are whether algorithms are ethical, depending on how they are trained and reinforced, the data sets they use, their possible biases and whether or not they are inclusive. It is also important to question the role of humans. Does big data, characterised primarily by its volume, speed and variety, requires the systematic use of AI, or is human processing sufficient and/or preferable?

A brief history of the development of AI

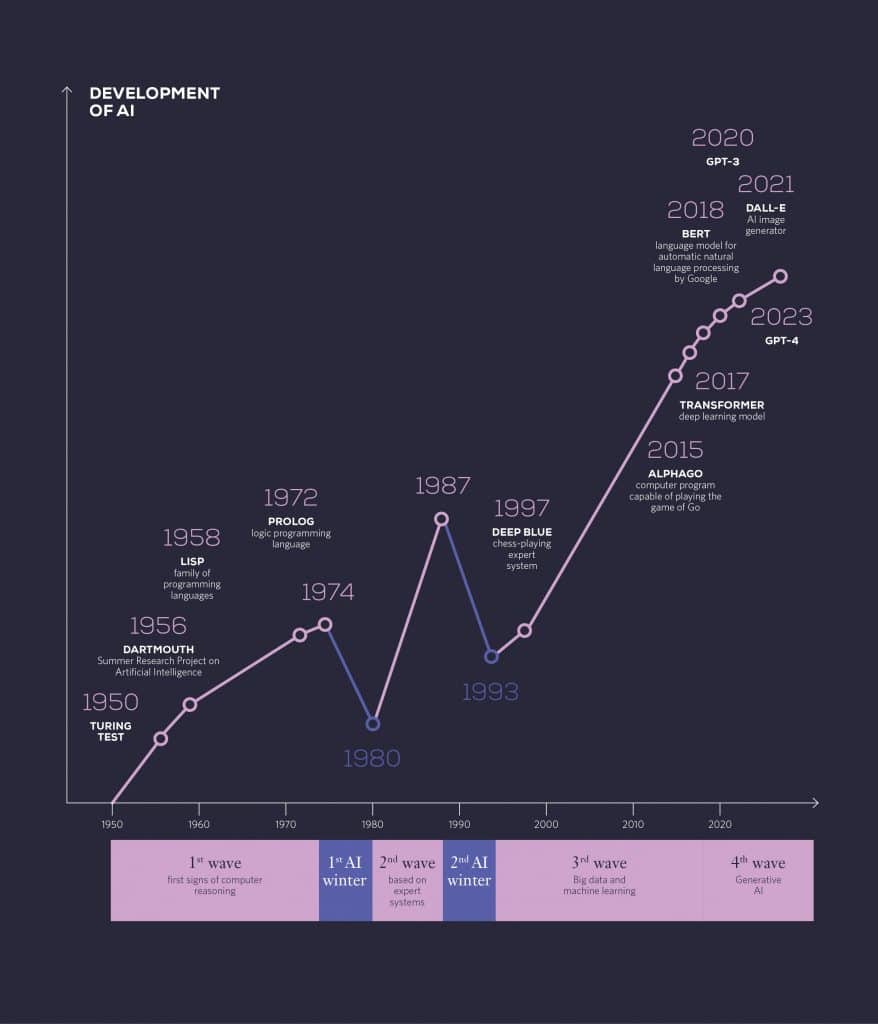

AI first appeared in the early 1950s with the first associated computer programming languages, such as LISP (designed for intelligent LISt Processing), and the famous Turing Test, which determines whether a machine has the ability to imitate a human conversation and thus pass as a human. After some over-inflated expectations as to its possible uses, AI suffered waves of backlash or disappointment, two so-called “AI winters”, and was then applied in fields that were narrower and more specialised than those initially envisaged or imagined.

More recently, neural networks made their appearance. Their capacity for self-learning and their ability to establish probabilistic correlations between data elements, combined with the computing power of machines, which according to Moore’s Law continues to double every 18 months, have significantly accelerated the rise of AI and its applications, with the corollary that the answers generated are both plausible and astonishing. Large language models (LLMs), which make it possible to implement this type of AI, are models trained on a large corpus of texts.

It is also legitimate to wonder whether we might experience a third AI winter in the medium term, just as the buzz and engagement generated by the metaverse has started to die down. However, where generative AI is concerned, the time horizon has accelerated. As an example, since January 2023, Sciences Po University in France has been requiring its students to “explicitly mention” any passage written by ChatGPT ; prohibition measures have also been taken in Italy2. Then, in March 2023, some of the founders of these systems requested a 6-month break in their development, fearing that humans would lose their control over machines. Finally, in the absence of fertile ground for the development of AI champions in Europe able to compete with the two digital superpowers, namely the United States and China, the European Parliament is preparing to introduce an AI Act in order to have a regulatory framework in place by the end of 2023.

We thought it would be useful at this stage to summarise the main developments in what is now known as “AI” in the graph below, up to the current period, with the addition of the so-called generative Ais.

Algorithms and ethics

How could algorithms be trained to decide what is ethical and what is not? Take for example a draft law, a best practice to apply, or a recruitment decision to be made for a vacant position. After a series of calculations and a cascade of sub-calculations – to break down a problem into sub-problems that are simpler to solve –, always making binary choices, a decision would be generated that qualifies as ethical. There are many questions to consider: who writes these algorithms? Who supervises their writing? Without there necessarily being any ill intent, the choices will obviously differ according to the writer or the initial training of the programmers and data scientists. Depending on how algorithms are designed, the way they are written can vary considerably, since there are myriad ways to write a program3. The cultural dimension of ethics is obvious, as is the choice of language. And more importantly, these binary approaches seem to lead to a loss of nuance, which is so important in ethics. One professor from the University of Bergen (Norway), during a conference at SKEMA Business School, suggested arriving at an ethical middle ground; yes, nuance will no doubt be overlooked at times, but in her view “that is the price to pay for decisions that work”4. Any weak signals are swept aside, as can be seen with ChatGPT, which is highly formatted and so politically correct that context is ignored. This political correctness leads to answers that are not exact but right from a probabilistic point of view, with a mixture of sources compiled on the Web without distinguishing relevant or respectable sources from those that are less so, and without integrating the time dimension that is so precious in data analysis.

This raises the issue of techno-solutionism, or turning to a technological tool as the first solution to any problem. The question of need is dismissed out of hand. Do we need this calculation method in order to define ethics? Techno-solutionism amounts to replacing a non-digital solution with a digital one, because it is digital, not because it meets a need. Telemedicine consultations are one example of this. They are useful when the consultation is for analysing results, but they are not useful in all circumstances. The question of consequences is not considered.

Given the profusion of content generated by AI, it could be worthwhile to flag up content produced exclusively by humans, as suggested in the 100% Human Content Charter launched at VivaTech 2023.

The following are some initial recommendations:

Recommendation 1: Given the risk of blind trust or potential user manipulation, a note should indicate that the answer has been generated by AI and is not necessarily accurate.

Recommendation 2: Ensure traceability of exchanges and, in addition to data portability, ensure portability of the prompts and the responses generated. Issues pertaining to the storage of these exchanges and to governing law must also be considered for reasons of sovereignty and economic intelligence.

Freedom as a component of ethics

One related issue is that of freedom, which is also an integral part of the ethical dimension of digital technology5. Does using digital technology lead to greater freedom or not? And in what ways? This is a question we should be asking ourselves constantly and it should guide the progress of digital technology and of society. For example, the growing use of electronic and cashless payment methods, under the guise of convenience, particularly with contactless payments, is reducing the use of cash, notes and coins: this leads to less freedom, such as the freedom to buy something from a flea market or to give to the homeless — although in China it is possible to donate via QR codes, etc. Worse still, it is the guarantee of being constantly tracked, and of new tracking tools being developed, with individual and collective consequences that cannot be ignored. The trend towards all-digital runs directly counter to the preservation of spaces of freedom. We are also thinking about the individual consequences of the development of the metaverse. We are thinking about sport and its virtual or augmented reality forms, which are increasingly being offered to us. No one seems to be asking these questions before developing the technologies. The question of consequences and possible regulation always comes afterwards. Ethical considerations – just like the development of positive law – run behind digital development to catch up, when it should be the opposite. This is an issue for governments, but few leaders are aware of it, sometimes due to questions of power.

This issue of freedom is all the more important since during the COVID-19 pandemic we saw citizens being denied access to restaurants and other places because their health or vaccination passes were not up to date. What would happen in the future if there were a convergence on our smartphones of a Health Pass, an Environmental Pass and a Payment Pass? A citizen who had used up their carbon credit, for example, might no longer be allowed to fly or take a train, even if they had enough money in their account. With this convergence and the end of cash, they would have no alternative means of payment. Underlying all this, there is undeniably the sensitive issue of cybersurveillance and the curtailing of freedoms6. This counterbalances the missions of the CNIL (the French Data Protection Authority) and the GDPR, which are being circumvented by the major platforms. Perhaps tomorrow they will be circumvented by governments in more subtle ways. The ease with which we can hand over our data in order to make better use of it must not be a source of alienation.

One other type of freedom is freedom of speech, which must be plural in a democracy within the framework of positive law. It is not a question of hate speech or abusive language being allowed to spread, particularly on social media where it is punished, but of the challenges presented by AI-powered moderation. The latter can arbitrarily ban content that uses humour and irony, for example, or that does not fit into a certain belief system, or it can even ban accounts from the platform in question. Two other recommendations follow:

Recommendation 3: Users should be given more detailed training and information about the storage of their personal data and compliance with legislation.

Recommendation 4: In the case of a high-impact decision such as banning someone from an online platform, a human supervisor should weigh in on the decision reached by AI, in order to achieve a fair outcome.

Finally, this freedom must be understood outside the realm of conscious expression. We are talking here about “neurorights“, i.e. the right of each individual not to be influenced in a totally surreptitious way by formulations or procedures linked to AI. This will be the subject of an upcoming study by SKEMA PUBLIKA.

The need to cut red tape

Another subject that raises similar questions is the red tape resulting from algorithms. We spend a great deal of time criticising bureaucracy and the rules that hem us in, but we do have the possibility of contesting these. We used to see this in the past, for example, when a parking fine was wrongly issued because a traffic warden had failed to see the pay-and-display ticket, or because the ticket had slipped off the dashboard into the car’s interior, or when a police officer could use discernment about whether a traffic light was red or amber depending on traffic and the vehicle’s speed. In these cases, we could provide evidence and plead our good faith. But what can we do about the algorithms that run our lives as citizens, manage our welfare benefits, our energy and even our food? From this point of view, just as we have good reason to be concerned about digital money becoming the only financial tool, having an administrative system that relies solely on AI without any human intervention is a risk: in the event of an appeal, an individual’s case could be dismissed even if they are in the right.

Any digital transformation must therefore include a manual mode for handling exceptions and also degraded modes for situations where AI cannot work. For example, the use of cash is a degraded mode compared to card payment, which can be practical. Other examples include cyberattacks, computer breakdowns or even rare maintenance operations that make AI use impossible.

Finally, following the repeated recommendations of governments to simplify the lives of citizens, and listening to the rhetoric of digital service providers, greater use of algorithms and AI should lead to simplifying and securing the lives of citizens and not the other way round. This is far from the case in some instances, where the much-vaunted ‘dematerialisation’ is leading to major delays in the issue of documents, particularly abroad, or to bugs in electoral processes, where everyday actions require the possession and mastery of a computer, or where the elimination of all human intervention exposes people to errors of assessment. The use of AI by government departments and businesses must not leave out individuals who do not have the means or the knowledge to access it. The real progress made by AI in medicine, for example, must not be used as an excuse for abuses.

Recommendation 5: Provide help with using AI, particularly to the most vulnerable people, whether it is to take care of administrative procedures or to lodge a dispute.

Recommendation 6: Any digital transformation must include degraded modes, in case of a power cut, for example, or of an area with limited network coverage, so that data can be collected and processed and the service can be maintained even if it is less efficient.

Recommendation 7: The introduction of fully automated procedures based on algorithms and AI should only be decided when there is a real, measured benefit for citizens and consumers (see below the recommendations of the Conseil d’État on the need for “benefit”). The benefit should also be multi-faceted: time saving, financial gain without being costly in environmental terms.

AI, algorithms and sustainable development

The amount of data consumed by algorithms can run counter to the need for energy efficiency and contribute to global warming or to other forms of pollution depending on available resources. One example that has been highlighted is the water consumption of the ChatGPT data centres (700,000 litres to train OpenAI’s GPT3 alone, and 500 ml per basic conversation between a user and the AI chatbot). And with each successive generation of GPT, the number of parameters is growing at a worryingly exponential rate. The most important question when it comes to serving the public is: “How will the technological solution increase satisfaction while meeting greater good requirements such as digital sobriety?”

It is also possible to design better performing algorithms at the outset, such as a sorting algorithm with an O(n log n) complexity instead of O(n * n). We need to come up with disruptive solutions. For example, the Hive solution uses the storage on web users’ computers and smartphones to offer a sovereign cloud solution that maximises the use of available resources rather than using data centres and disk arrays, bearing in mind that nearly 50% of a data centre’s energy consumption is linked to its management (cooling, etc.).

Recommendation 8: Find solutions for frugal algorithms that perform better and consume less energy, for example using less data to arrive at the same result, or offering reduced performance but using fewer resources.

Establishing principles applicable to AI

A March 2022 report by the French Council of State (Conseil d’État) presents a number of possible avenues. In France, the government must be able to demonstrate that its decision to use an AI system and the operating processes it has defined are guided by an objective to benefit all people. Consequently, it must guarantee accessibility to all.

Fulfilling the human benefit requirement implies looking beyond immediacy to analyse the long-term consequences of the system. And this must be done when the law is being drafted.

The report of the French Council of State mentions the principle of purpose limitation. For example, personal data must be processed in a manner compatible with the purposes for which it was collected.

At the international level, the WHO issued its first global report on AI in health, the main principles of which can be transposed to other sectors. It identifies six guiding principles for its design and use: protecting human autonomy; promoting human well-being and safety and the public interest; ensuring transparency, explainability and intelligibility; fostering responsibility and accountability; ensuring inclusiveness and equity; and promoting AI that is responsive and sustainable.

Finally, the question of data lies at the heart of these issues, because data is a new raw material. Like traditional raw materials, it gives rise to enormous and sometimes unfair competition, as well as to predation, as happens with natural resources. There should always be protective laws in place to manage data: protective against unethical testing, such as medical data, and protective against life tracking, not just from the point of view of privacy protection, but also from the point of view of the purpose for which data is used. In this respect, countries such as France that are rich in medical data are prime targets. AI makes it all the more important to respond to these issues, which in reality are a matter for political decisions.

In practical terms, general ethical considerations must inspire operational ethical considerations, by ensuring that the ethical dimension is taken into account from the technical design stage through to the deployment of the digital solutions by duly informed teams. This “ethics by design” concept should not be random and left to the sole judgement of those who write the algorithms, but should meet standards that are sufficiently broad not to become rigid new imperatives. To paraphrase a maxim that originally applied to the army: digitalisation is too important to be left solely to digitalisers.

How can these principles be established?

Today, a multitude of players and just as many initiatives are concerned with the subject of ethics and AI, as indicated and detailed in a June 2023 article by M. Gornett and W. Maxwell, who remind us in passing that the French Larousse dictionary defines the adjective ethics as “concerning morality”, while the Robert adds “incorporating moral criteria into its operation“.

The authors also remind us that the coexistence of European and international standards conceals geopolitical issues and that, in addition to these supranational initiatives, many others are being developed by professional bodies, private standardisation organisations and even companies.

Should these initiatives be left to develop or should a global framework of responsibility be sought? With the risks associated with a single global governance system?

Today, at the multilateral global level, UNESCO has taken a definite lead by issuing a Recommendation on the Ethics of Artificial Intelligence in November 2021, which was adopted by UNESCO’s 193 Member States. According to the UN organisation, this is “the first-ever global standard-setting instrument on the subject, which will not only protect but also promote human rights and human dignity, and will provide an ethical compass and a global normative foundation for building strong respect for the rule of law in the digital world”. In June 2023, these principles were the subject of a workshop at the AfricAI Conference in Kigali, Rwanda, to discuss its Capacity Building Framework on Digital Transformation in Africa and India.

At the international standards level, ISO has a sub-committee SC 42, Artificial Intelligence, which aims to create an ethical AI society. This is a field that involves a quasi-political confrontation between objectives of influence and, once the standard has been established, certification systems that will undoubtedly represent major business opportunities for the organisations providing the services.

We cannot fail to mention the French debate, which is at a very advanced stage, in particular the opinion issued on 30 June 2023 by the French National Committee for Digital Ethics (CNPEN), which sets out a number of recommendations to govern the development of generative artificial intelligence software, such as ChatGPT. This text targets the risks of manipulation or disinformation. It also proposes a principle that we mentioned above, even if it has a different name, which is to ensure common ethics in the very design of algorithms, and proposes a European regulation for this purpose, the basis of which already exists.

There is an urgent need for democratic governments to address these issues in conjunction with representants of the civil society and parliamentary assemblies. Much has already been done to manage the digitalisation of society without asking them for their opinion. Let’s seize the development of AI as an opportunity to improve the social contract between citizens and the State. The democratic State has legitimate powers as long as it meets the needs of its citizens, specifically the need to protect them.

- Launched on 30 November 2022. Within just five days, one million accounts had been created. Never before had a technology achieved such a milestone in such a short time. ↩︎

- On 31 March 2023, Italy’s data protection watchdog, the Garante per la protezione dei dati personali, decided to temporarily and immediately ban access to ChatGPT and OpenAI in response to suspected privacy breaches. ↩︎

- The Art of Computer Programming, Donald E. Knuth, Addison-Wesley, 1968-2022. ↩︎

- “The world is ‘colourful’, whereas computers only read ‘black and white’ [..]. To use an algorithm, the rules and the moral information need to be specified in a formal language. Formal here just means unambiguous. […] I do think ambiguity is useful but we do not have the luxury of it when making computer programs.” ↩︎

- One of the themes of the “Ethics and Respect in the Metaverse” conference held on 24 November 2022 and organised by the NGOs Institution Citoyenne and Respect Zone. ↩︎

- Adieu la liberté. Essai sur la société disciplinaire. Mathieu Slama, Presse de la Cité, 2022. ↩︎