This work alerts on an issue that is still relatively un-known to decision-makers, and is on the cusp of national and international regulation.

Some time ago, the expectation of mind invasion or manipulation of people by technological devices was only seen in movies and science fiction books. Examples included erasing people’s memories in Men in Black, modifying the behavior of criminals in Clockwork Orange, and arresting people who are about to commit a crime in Minority Report, all of which entertained and invited people to reflect on the future.

Today, the massive flow of data and advances in science, particularly in neurotechnologies and artificial intelligence, have made these concepts an emerging field that requires further study and regulation by the legal community. Neurorights are a new field of study, with a global research movement that has emerged and has been addressed in a pioneering way by scholars who study the intersection of law and neuroscience. Advanced technologies, such as brain-machine interfaces, wearable and implantable devices, and advanced algorithms, have made neurolaw an increasingly important field.

Neurolaw: the emergence of a new field

Although neuroscience has been around for over 100 years, it has rapidly developed in the last two decades with the introduction of real-time brain imaging devices. The relationship between law and neuroscience dates to that period. The article “The Brain on the Stand,” by Francis X. Shen published in 2007 in the New York Times Magazine, is a milestone for the emergence of Neurolaw in the USA.

Indeed, criminal law appears to be the first and most explored point of contact between neuroscience and law, so much so that in 2009, Jan Christoph Bublitz and Reinhard Merkel, two German authors from the criminal area, presented a paper in which they questioned the “illegitimate influence” of third parties (through direct interventions, such as pharmaceuticals, and indirect interventions, such as hypnosis and subliminal advertising) as a factor to be considered in trials, which led the researchers to also consider the rights of the person under influence and argue that their rights to autonomy and authenticity had been violated by external interventions.

Another important article from 2012 by Nita Farahany addressed the advances of neuroscience in the courts and discussed the need for a new taxonomy for the principle of non-self-incrimination. She argued that the protection of this principle usually refers to the protection of what people say and suggested that “a society interested in robust cognitive freedom would probably wish to protect its citizens from the unwarranted detection of automatic, memorialized, proffered evidence in the brain.” In this sense, Farahany questioned the risk of the judiciary misjudging the issue and suggested the need for a standard, a “Neuroscience Information Technology Act,” that would protect mental privacy and cognitive freedom. This document was important in giving a name to these rights and served as a milestone for the emergence of a movement in favor of neurorights.

In 2014, Bublitz and Merkel, now well-known authors in the consolidating field of neurolaw, innovated by transposing the debate from the realm of criminal law to the realm of consumer law. They questioned the need to protect the rights of people who may be manipulated by industries that study and influence decision-making, as represented today by social media. The question demonstrates a new direction of research, which shifts the focus from the concern with the judicial system and the guarantees inherent to it, to the person and their neurorights violated in everyday life.

What risks do neuroscience and neurotechnologies pose?

Data and information generated by brain activity, which is commonly known as neural data, can be accessed through neurotechnology, including non-invasive methods such as the analysis of typing patterns. Neural data provides valuable information that, without proper regulation, could potentially be used for manipulation, such as targeted advertising or other interests.

The OECD, in a 2019 recommendation on the responsible use of neurotechnologies recognizes that “neurotechnology raises several unique ethical, legal, and social issues that potential commercial models will have to address”.

That same year, the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe called “attention to the growing threat to the right of human beings to form opinions and make decisions independently of automated systems emanating from advanced digital technologies”.

It is important to note that artificial intelligence (AI), when used to influence decisions, becomes a non-invasive method of mind manipulation, which can be considered a threat to cognitive freedom and mental privacy. Some examples of this manipulation are:

- Hypernudging, a version of nudging, a manipulation based on behavioral economics, which uses data and artificial intelligence to indirectly read minds and to micro-direct people’s actions, which infringes upon values such as cognitive freedom, mental privacy, mental integrity, psychological continuity, and identity. (SHINER; O’CALLAGHAN, 2021)

- The inhibiting effects of new technologies and technological surveillance, whereby user’s behavior to exercise their legal freedoms or engage in legitimate activities is inhibited for fear of being watched at any time. (SHINER; O’CALLAGHAN, 2021)

- Profiling, the systematic and purposeful recording and classification of data related to individuals, which is compiled for the purpose of classification and clustering into categories. Profiling can lead to customization, ie. the result of indirect pressure for conformity to supposed standards of behavior. When the government draws up profiles, people may tend to fit one model or another, and the same can happen when category-based private rankings (such as insurance companies, banks, and health companies) push human beings into certain groups. This customization also occurs in politics and is a risk to democracy, as people may stop producing and seeking information that they would share if they were not being monitored due to concerns about being classified as too radical or too exempt. (Büchi, Fosch-Villaronga, Lutz, Tamò-Larrieux, Velidi and Viljoen, 2020)

- Profiling can also lead to de-individualization and the creation of stereotypes (Schermer, 2013)

- Informational asymmetry, loss of accuracy, potential abuse (fraud), and discrimination. (Schermer, 2013).

Behavioral manipulation differs from persuasion, which is explicit, and coercion, which explicitly confronts individual freedoms. Manipulation is a covert subversion of people’s decision-making power that exploits their cognitive or affective weaknesses.

This manipulation is a subtle form of control that affects the ability to choose, or agency. The expansion of social media, the use of big data, profiling, and AI create an unprecedented level of digital mediation (mediation between person and the real world, such as advertising, government propaganda, and electoral propaganda), and this medium – the data-driven, AI-managed electronic systems – is not neutral. Whether based on commercial, electoral, or even state domination interests, these systems can seek to subvert people’s behavior and their cognitive freedom.

A taxonomy of neurorights

Rights related to the neuroscientific effects of AI are a concern of the neurobiologist Rafael Yuste and his group of scholars at Columbia University. In the influential 2017 Nature article, titled “Four ethical priorities for neurotechnologies and AI“, Yuste and his more than 20 co-authors proposed the four priorities that led to the current development of neurorights : (a) privacy and consent, (b) agency and identity, (c) augmentation, and (d) biases. Then, in a 2021 article titled “It’s time for neurorights”, Yuste and his collegues created an updated list of neurorights :

- the right to identity, or the ability to control both physical and mental integrity;

- the right to act [agency], or the freedom of thought and free will to choose one’s own actions;

- the right to mental privacy, or the ability to keep one’s thoughts protected from disclosure;

- the right to fair access to mental enhancement, or the ability to ensure that the benefits of improvements in sensory and mental capacity through neurotechnology are fairly distributed in the population; and

- the right to protection from algorithmic bias, or the ability to ensure that technologies that use big data and AI do not introduce bias.

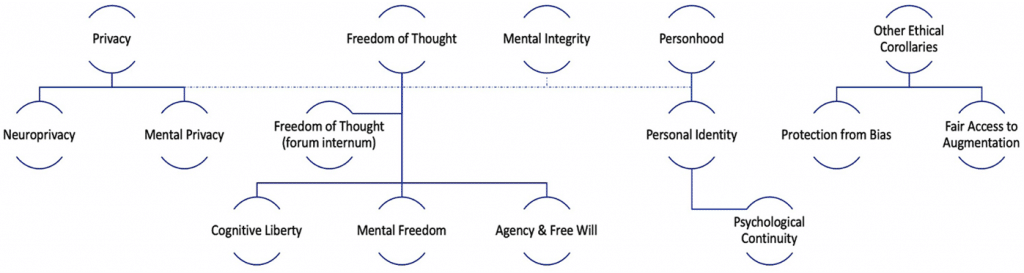

That same year, Marcello Ienca offered a full classification of neurorights:

Since 2007, neurorights have been consolidating as a new set of human rights, which today are already outlined and being implemented by some countries.

Enacting neurorights into law

They are two legal approaches on the subject: one prefers updating the interpretation of already existing norms, drafted before contemporary developments of AI and new neurotechnologies; the other, apparently more adequate, proposes new human rights in the face of challenges to mental and psychic integrity, as well as to the identity and autonomy of individuals.

a) New judicial interpretations of existing rights

Historically, national and international law have dealt with the defense of cognitive freedom, mental privacy, and freedom of action.

In criminal law, for example, the principle of non-self-incrimination can be analysed through the lenses of neurorights. In 2012, Nita Farahany expressed the need for a clear definition of the deponent/accused’s neurorights, and argued that the discussion of non-self-incrimination must include mental privacy, even without considering neurotechnological apparatus.

In consumer law, there is concern that the supplier can take advantage of psychological weaknesses in the consumer to benefit from the informational asymmetry. This manipulation is a kind of “version 0.1” of the current algorithmic manipulation. Unfair terms are considered unfair because they exploit cognitive limitations, as does irregular advertising. Furthermore, in addition to informational asymmetry, Consumer Law has always been concerned with the psychological vulnerability of consumers.

More recently, the issue of bullying – as dealt with in Brazilian Law 13.185/2915 – refers to “physical or psychological violence in acts of intimidation, humiliation, or discrimination,” i.e., systematic bullying. At that time, a concern with people’s mental integrity could be observed, even when the bullying occurred in the online world (cyberbullying).

The 2021 Brazilian legislation on over-indebtedness, Law 14.181/2021, which is also a consumerist issue, highlights another aspect of the violation of cognitive freedom. Art. 54-C, included in the Consumer Protection Code, prohibits credit advertising that may “conceal or make it difficult to understand” for people, as well as advertising that “harasses or pressures the consumer to contract.” In these cases, cognitive freedom, especially that of the most vulnerable, such as the sick and the elderly, is the actual protected legal right. The innovation was necessary because here there is no coercion in the classical sense or even explicit persuasion; instead, there is manipulation through advertising designed to subvert the power of choice.

This concern with the defense of psychological weaknesses is already close to the theory of neurorights, which are existing rights that could be considered as the first stage of concern for mental privacy (the principle of non-self-incrimination); for mental integrity (the anti-bullying rule); and for cognitive freedom (consumer law and against over-indebtedness).

Similarly, in international law, two articles of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights indicate the need for the protection of neurorights. Article 18 states that “Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience, and religion”. Article 22 mentions the right to dignity the free development of personality.

Those can be considered first-generation neurorights. However, more specific rights are now required. The development of neural devices and technologies, artificial intelligence, and massive data collection, particularly on the internet and social media, require rights that directly protect psychic health, the mind, and neural data.

b) Neurorights in national and international law

Protecting neural data and other personal data that could reveal weaknesses and aspects of individuals’ behavior is necessary to safeguard mental or psychic integrity in this new scenario. In this sense, the Brazilian proposal for a contemporary and specific treatment of the subject, included in Bill 1.229/2021, initially deals with the protection of neural data within the General Law of Data Protection, systematizing the protection of people’s digital body and mind.

The Brazilian proposal introduces some interesting concepts and proposes a basic definition for neural data: “any information obtained, directly or indirectly, from the activity of the central nervous system, and whose access is gained through invasive or non-invasive brain-computer interfaces” (proposed for Art. 5, XX). Additionally, the proposal suggests that: “The request for consent for the processing of neural data must indicate, clearly and prominently, the possible physical, cognitive and emotional effects of its application, the rights of the holder and the duties of the controller and operator, the contraindications as well as the rules on privacy and the information security measures adopted.” (Proposed Article 13-D)

The text is good, although it does not explicitly address the use of data extracted through web browsing. However, even without explicit rules, it is possible to extend the proposed text to AI systems and social network data, since “non-invasive interfaces” and “indirect” obtaining of data are covered. This way, the new rules would be appropriate to provide basic protection for even the most current neurorights.

Another example of existing rules is the Spanish Digital Rights Charter, which included a chapter on digital rights in the use of neurotechnologies. The document, discussed since 2020, should enter into force by 2025 and contains, besides the explicit reference to neurorights, articles that deal specifically with digital identity and other related topics such as anonymity and equality. In addition, some rules about the use of artificial intelligence will be very relevant for the defense of neurorights related to the use of this tool. There are rules about non-discrimination, transparency, and the right not to be subjected to algorithmic decisions or to challenge them when they occur.

Finally, the Spanish Charter for Digital Rights also addresses protection against manipulation, which is crucial for safeguarding neurorights, in an article specific to rights as regards artificial intelligence: “The use of AI systems aimed at psychologically manipulating or disturbing persons, in any aspect affecting fundamental rights, is prohibited”.

In the 2017 Nature article mentioned above, Rafael Yuste and his collaborators suggest an “International Declaration on Neurorights and an International Convention” with greater effectiveness. They criticize the current consent forms, which only address physical risks, and propose implementing education about the possible cognitive and emotional effects of neurotechnologies in a global document. At UNESCO International Conference on Ethics of Neurotechnology, last July 2023, Rafael Yuste declared that “The conclusion [of our research analysis of the consumer user agreement of 18 major neurotechnology companies in the world] is that there is a complete lack of protection, in fact, you cannot imagine less protection to brain data.” The conference advanced the idea of “a comprehensive governance framework to harness the potential of neurotechnology and address the risks it presents to societies”, and the need for “a global normative instrument and ethical framework similar to UNESCO’s Recommendation on the Ethics of Artificial Intelligence.”

Conclusion : Neurorights for human dignity

The dignified existence of the human being is a basic principle of many modern constitutions. To exist in a legally dignified way is, on the one hand, to always be a person and never an object of relationships and, on the other hand, to have minimum socioeconomic conditions for living.

Studies on neurorights point out that human dignity is being challenged by several new techniques, invasive or not, that may hinder the exercise of human autonomy and agency, reducing the person to an object, without desire or with externally induced desires. A robot from old movies, whose thoughts are mere unfolding’s of pre-programmed commands.

New knowledge and existing proposals for solutions are important tools to address these issues and even new challenges posed by technologies based on big data and artificial intelligence.