The Cross of Saint George and Other Divisive Symbols

There’s not too long to go before the fans of teams competing at the World Cup start appearing on the streets of Doha. Among them will be England supporters, who will undoubtedly be wearing their team’s shirts and carrying flags – both of which will be adorned with the Cross of Saint George.

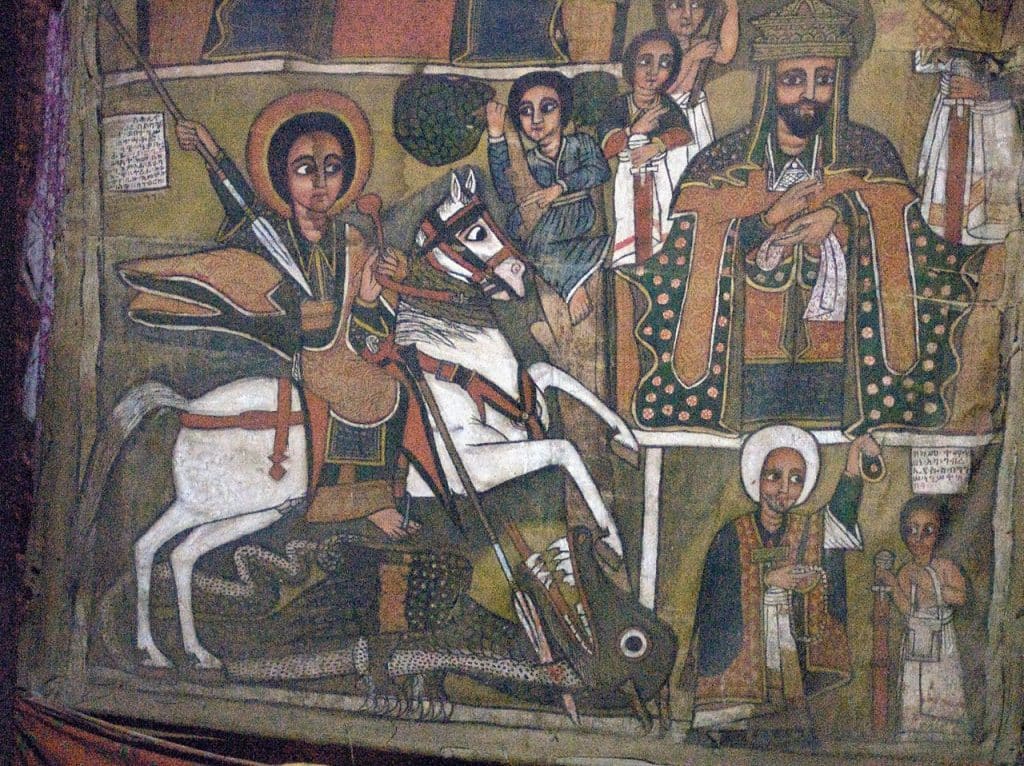

It sometimes seems strange that some English people are obsessed with the symbols of their patron saint: actually, George was a Cappadocian Greek born in what is now Turkey. Still, there are others who share such veneration; Ethiopia, Georgia and in Spain both Catalonia and Aragon, also all claim him as their saint.

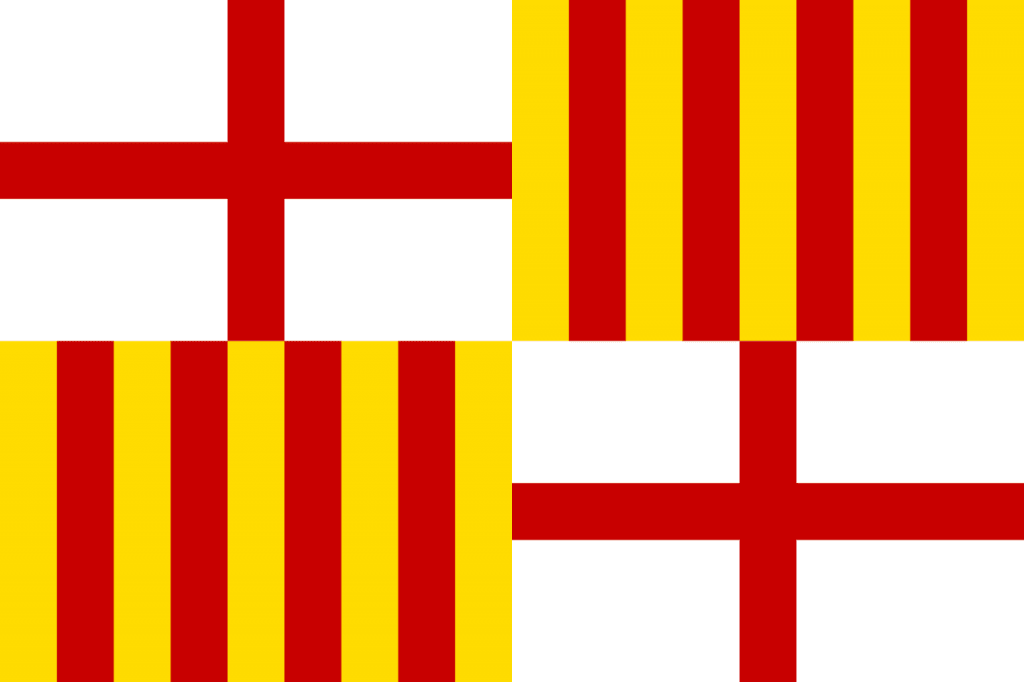

Others view it in different terms, particularly because Saint George’s Cross is a symbol that has become synonymous with the Christian crusades, during which up to one million Muslims are believed to have been killed. In the past, this has caused some problems for the likes of FC Barcelona.

The city is capital of Catalonia hence the cross appears in the football’s club’s badge. In previous decades, there have been instances when the club was asked to modify its official badge ahead of playing matches in the Gulf region. Indeed, in some of the region’s online discussion forums there have been intense debates about whether teams that display the Saint George Cross are ‘haram’.

Whether it’s England, FC Barcelona or another team, it therefore seems obvious and inevitable that what some might see as being acceptable as a symbol, others don’t. But it’s not just symbols that are potentially divisive, letters and words can be as well. Already this year, we have witnessed a single letter – Z – causing all manner of issues, even in sport.

Although it remains somewhat unclear what the letter is supposed to mean, it has adorned Russian military vehicles used to invade Ukraine. Several athletes subsequently adopted the symbol, publicly displaying it during competition. In Doha earlier this year at the gymnastics World Cup, bronze medal winning Russian Ivan Kuliak taped the letter Z to his vest as he appeared on the winner’s podium alongside Ukrainian Illia Kovtun.

The International Gymnastics Federation condemned this display as shocking, and subsequently banned Kuliak from competition and commenced disciplinary proceedings against him. In response, the gymnast stressed, “If there was a second chance, I would do the same; I saw it on our military and looked at what this symbol means. It turned out to be ‘for victory’ and ‘for peace’.”

Rainbow flags, Human Rights and Conflicting Values

The multiple meanings that people attribute to symbols will again manifest themselves in Qatar once the FIFA World Cup starts. Already, there has been an intense debate about rainbow flags, badges and even team captains’ arm bands. Over the last decade, the rainbow symbol has become ubiquitous in liberal societies, a display of support for LGBTQ+ rights and identity.

For instance, last year during the UEFA European Championship, the Mayor of Munich wanted the city’s Allianz Arena to be lit in rainbow colours for a game involving Hungary. This was intended as a protest aimed at the country’s president (Viktor Orbán) and his discriminatory treatment of LGBTQ+ communities in the central European nation, though UEFA refused this request.

FIFA and Qatari tournament organisers have agreed that rainbow flags will be permitted inside stadiums, an important measure for football’s world governing body which seeks to promote tolerance and inclusion. Whatever such displays may, or may not, achieve, many fans from countries such as Denmark, the United States and Brazil will see their flying of LGBTQ+ flags as a basic human right rather than a special dispensation.

However, this doesn’t mean that controversy has been averted; in April, Qatar’s Major General Abdulaziz Abdullah Al Ansari warned visiting fans against public displays of LGBTQ+ symbols. He has been reported as having said, “If he [a fan] raised the rainbow flag and I took it from him, it’s not because I really want to, really, take it, to really insult him, but to protect him – somebody else around him might attack [him], I cannot guarantee the behavior of the whole people.”

Perhaps Al Ansari’s words are not without some foundation. Following a presentation that I gave in Qatar just before the pandemic, a Qatari senior told me, “I don’t want the World Cup in my country because it threatens my Islamic beliefs. I don’t want to see people holding hands or kissing in public, nor do I want people to see people of the same gender in relations together.”

Symbols in International Competitions: Who holds the Moral Compass?

The last 30 years have been characterised by unprecedented changes, amongst them globalisation and digitalisation. More than ever as citizens of the world, we are being exposed to new ways of living, consuming, and communicating. No longer is it a world in which a small number of nations dictate a prevailing hegemony, nor is it a world in which we can readily protect ourselves from alterative or opposing views.

This means that the likes of football tournaments are increasingly held in countries that hitherto haven’t played hosts, which brings unfamiliar values, norms, and conventions to their staging. At the same time, host countries find themselves talked about in ways they perhaps didn’t anticipate or confronted with ways of living that may seem threatening.

In these circumstances, seemingly innocent symbols and signs can become ideologically, politically and socio-culturally charged, challenging many of us either to confront what offends us or to modify our views of what we think is acceptable. This type of process is never short, attitudes tend to change between generations rather than within them.

Which means that in the meantime, governing bodies, event organisers, clubs, teams, athletes and sponsors are typically left to serve as the arbiters of what is acceptable and what is not. This is a tough task for them, although we do have various United Nations standards that may serve to underpin a collective sense of how signs and symbols are used.

One imagines that the letter Z won’t make an appearance at the FIFA World Cup, though the Saint George’s Cross and the LGBTQ+ rainbow will as, presumably, other symbols and signs that people have issues with will. But in our globalised, digitalised world, who ultimately decides what is or isn’t acceptable?