The devastating conflict raging in Ukraine since 24 February has turned into an all-out war in this country and is prompting an unexpected and risky geopolitical reshuffle of the European continent. This is because the agenda and interests of the European Union are perhaps not shared by NATO and the United States. Maintaining a strong stance against Moscow is necessary, but with the aim of negotiating to establish a lasting peace guaranteeing the stability of Europe.

How things stand after several months of conflict

In February 2022, Russia had a clear invasion strategy: seize Kyiv, topple President Zelensky, and install a regime favourable to Moscow. But this plan backfired; Russia was unsuccessful in taking Kyiv. As the New York Times demonstrated in a fascinating analysis, the Kremlin’s strategists underestimated the resistance of the Ukrainian people and the determination of their president, and overlooked the Russian army’s lack of experience in large-scale urban combat. After this epic failure, Russia deployed a new strategy aimed at overpowering the east and south of Ukraine in a trench war reminiscent of World War I.

Its troops stopped at nothing as they destroyed major Ukrainian cities and attacked civilians, all the while engaging in systematic disinformation about the reality of the conflict. According to Amnesty International, there is compelling evidence of war crimes committed by the Russian troops. The International Criminal Court is conducting a thorough investigation to establish the facts.

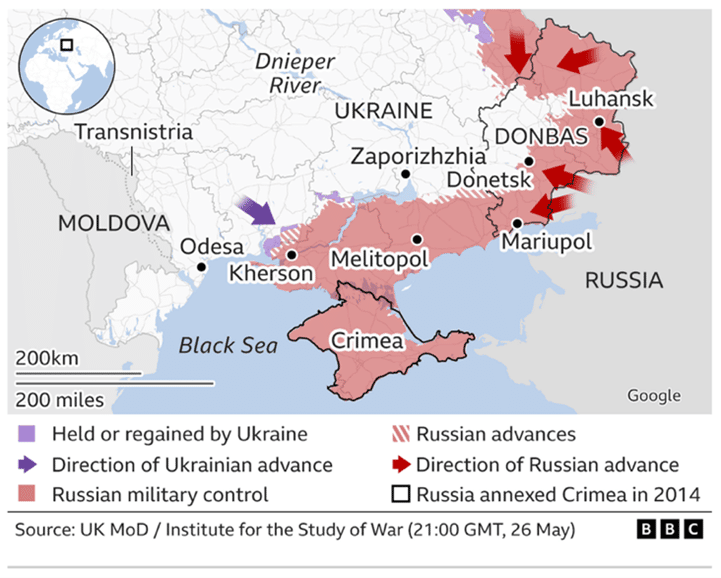

Moscow has several geopolitical ambitions: gain permanent control of the Donbas, control access to the Sea of Azov, tie Crimea to Russia, cut off Ukraine’s access to the sea, and, ultimately, form a bridge between Russia and Transnistria, a Moldovian province whose autonomy Moscow supports. In a previous article, we emphasised that, fuelled by hostility toward the West, Vladimir Putin was seeking to rebuild Great Russia. If he cannot take Ukraine, its partial dismemberment will at least be celebrated as a victory.

The death toll on the Russian side is also huge. It is reasonable to think that Russia had lost between 10,000 and 12,000 soldiers by mid-May. This estimate means that these first months of war have cost at least as many lives as the ten years of conflict in Afghanistan. The reason is that the balance of power, which initially tipped toward Russia, has now shifted. Ukraine may have only ranked 22nd worldwide in terms of military might, but its armed forces, backed by a population now hostile to Russia, are now heavily armed by the West, whereas Russia is now reduced to using weapons from the Soviet era and sending inexperienced conscripts to fight. As noted by The Economist, although the Russian army is the world’s second military power on paper, in reality it is “in a woeful state”. On the Ukrainian side, the death toll is similar, with likely 15,000 civilian and military deaths by mid-May.

At the time of writing this article, it would thus appear that the war Vladimir Putin started against Ukraine has failed on three levels. The offensive has not achieved its strategic objectives; it has reinvigorated the Atlantic alliance – membership applications from Finland and Sweden had been unthinkable before now – from which the United States was pulling away; and it has sparked a strong European reaction. The war in Ukraine is a dramatic example of the paradoxes of strategy presented by Edward Luttwak.

A conflict and its contradictions

In addition, the conflict has revealed a number of points of convergence but also of contradictions amid its stakeholders. The points of convergence have been spectacular. The scale and determination of the European Union’s reaction surprised Washington. Despite some diverging positions, such as that of Viktor Orban, and the initial reticence of certain countries such as Germany, in connection with Russian gas supplies, the EU took a series of unprecedented measures combining arms deliveries to Ukraine, sanctions, and even plans for an embargo on Russian hydrocarbons. Note in passing that the Russian invasion came as such a major shock that Chancellor Scholz did not hesitate to make a U-turn on almost 80 years of German pacifism by announcing a plan to arm Ukraine. As for Washington, it has massively armed the Ukrainian regime.

While less immediately obvious, the contradictions borne by the conflict will be key in determining its future. On the Russian side, for example, Vladimir Putin’s assertion that Russians and Ukrainians are “one people – a single whole” (the similarity between the Russian and Ukrainians languages should not lead to the conclusion that they are a single people, since the history of the two countries is one of progressive differentiation over the last millennium) is in radical contradiction with the strategy of mass destruction Moscow’s troops have been pursuing since February. This speech, which aimed to justify a rapid strike, has simply become untenable in the context of a war whose primary victims are the Ukrainian people themselves. In fact, the real cultural and emotional ties that bind Russians and Ukrainians probably explain why the morale of Russian troops has never been so low as in recent weeks; it is difficult to bear the massacre of one’s own family…

On the European Union side, one glaring contradiction, which will be difficult to explain to future generations of students, is that the countries of Europe are arming Ukraine with one hand, but financing Russia with the other. Even though the EU 27 announced an embargo on Russian hydrocarbons on 31 May, this will take weeks if not months to take full effect, unless Vladimir Putin decides, as he seems to be doing, to cut off gas supplies to Europe. The fact remains that, since the beginning of the conflict, the EU has paid Moscow 55 billion US dollars in exchange for hydrocarbons. Note that Russia’s military budget is around 60 billion dollars… According to Margrethe Vestager, the reason for such a situation is not the naivety of Europeans, but rather their greed!

Insurmountable political and geopolitical differences

Finally – and this is probably one of the most significant hurdles for the future –, strong differences of opinion are beginning to rock what is being called the “Western camp”, namely the European Union and the United States. The use of the term “genocide” is dividing its leaders: while France refuses to use it, the United States and Poland, for example, have not hesitated to do so. Hidden behind these differences of opinion over an emotionally-charged term are very different war objectives which potentially carry risks for the next phase of the conflict.

There are two opposing camps: the United States, Poland and the Baltic states have adopted a hawkish position; they want a Russian defeat and for Kyiv to recover all Ukrainian territory. In contrast, France, Germany and Italy, among others, are trying to placate Moscow and maintain diplomatic ties even if that means ruffling some feathers. On 28 May, President Macron and Chancellor Scholz did not hesitate to ask Putin to hold “direct, serious negotiations” with Zelensky with, as a possible consequence, the surrender by Kyiv of all or part of the Donbas, a concession which, for now, is unacceptable to the Ukrainian president, who reacted by openly criticising France.

Finally, let us not forget the global geopolitical situation, which now tends to show the world as split into two camps, the “pro-Western” and the others, either supporters of Russia or “non aligned”. The vote at the UN on 2 March 2022, for a resolution demanding that Russia immediately end its military operations in Ukraine, revealed this new map of the world: granted, only five countries supported Russia; but 35 abstained, including the world’s two demographic superpowers, China and India, followed by a large portion of Africa.

A risk of uncontrolled escalation

One of the risks of the colossal US military support to Ukraine, delivered by the most fiercely anti-Russian states in the EU, is that the Ukraine war will lead Europe into an escalation of events with uncontrollable and disastrous consequences. The risk that the crisis will spiral out of control is very real; it has been raised not by enemies of the United States but by actual Americans who could hardly be suspected of staunch Russophilia. Among them are the economist Jeffrey Sachs and the former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger.

Jeffrey Sachs – who, in the 1990s, had been dispatched by Washington to advise Boris Yeltsin on his policy for a transition towards capitalism – has sharply criticised Joe Biden’s policy of pushing Ukraine to “defeat Putin” as “madness” (rather imprudently, had Biden not stated during a press conference in Warsaw on 26 March that Putin “cannot remain in power”?). He feels that the response to the unilateral Russian offensive needs to involve diplomacy and negotiation, two avenues abandoned by Washington where “hubris and shortsightedness” prevail. This argument, from an insider who knows the system very well, cannot be so easily dismissed.

In the same vein, Henry Kissinger, a guest at the Davos forum held at the end of May, spoke in favour of reaching a peace deal, even if that means Ukraine has to give up part of its eastern territories to Russia. In his view, failing to restart negotiations could have potentially disastrous consequences for Europe’s stability in the long term. Admittedly, Nixon’s now-98-year-old former secretary of state, who was born in Germany in the early 1920s, lived through the darkest hours of the 20th century in Europe and experienced first-hand how easily the continent was overcome by the most dramatic events in modern history…

The main reason explaining these two reactions is that the war in Ukraine has the potential to trigger a dangerous chain of events. The question of where the boundary lies between giving legitimate aid to a country under attack and cobelligerency is indeed valid, but the fact that the latter concept is not enshrined in the Law of Armed Conflict makes its appreciation subjective. Remember that article 51 of the United Nations Charter establishes rules regarding the use of force: supplying arms to a country under attack is considered participating in collective self-defence.

In fact, as underlined by Julia Grignon, Professor of International Humanitarian Law at Laval University, “financing, equipping, for example through arms transfers, providing intelligence or training armed forces other than its own (…) do not make it possible to conclude that a State may be considered as a party to an international armed conflict, and therefore as a cobelligerent.” She adds that, “if delivering arms to Ukraine or providing them with financial aid for weapons were considered to make France cobelligerent, the country would be permanently at war, because it is constantly supplying weapons to other states at war.”

Military aid – for war or for peace?

While this argument might be valid from a legal standpoint, the same cannot be said from a political and psychological point of view. Indeed, just how much can military aid to Ukraine be increased without escalating the conflict to the point of sparking a regional war with Europe as its theatre? It is worth noting here that Joe Biden called on Congress to pass a nearly $40 billion Ukrainian aid bill – equivalent to two-thirds of Russia’s military budget! – which represents an unprecedented effort in the post-Cold War era. The American president was careful to emphasise that the arms delivered to Kyiv were only to be used in Ukraine and never to target Russia, adding that “we do not seek a war between NATO and Russia. As much as I disagree with Mr. Putin, and find his actions an outrage, the United States will not try to bring about his ouster in Moscow.”

America’s intransigence after several months of battle can and should raise questions. The conflict is not taking place near their borders; this apparent distance might explain why the Americans are antagonising Russia so much and, with the help of Poland and the Baltic states, providing so much support to Ukrainian forces. The American military aid also serves as a warning to China, which is now tightening its grip on Taiwan.

Finally, it is possible that Washington has learned lessons from the wait-and-see approach it adopted in Syria when faced with the coalition formed by Bashar al-Assad and Vladimir Putin (although Barack Obama stated that a red line had been crossed, he backed away from using force) and now does not want to waiver. But this is a high-risk strategy despite what certain North American backroom influencers may think, namely that an escalation to World War III is impossible. Add to this Sweden and especially Finland’s request for a fast-tracked application to join NATO and this is obviously enough to give a paranoid Kremlin the impression that the West seeks the demise of Great Russia.

Whether he is bluffing or not, Vladimir Putin has already warned that massive arms deliveries could prompt Moscow to take punitive measures. One could always argue that the risk is low; that China, an ardent supporter of Russia, has nothing to gain from a world war… but when does anyone ever gain from war? As historians well know, conflicts are often sparked by absurd, irrational decisions! And remember that, as recently as mid-February, many geopolitical experts were still saying that a Russian attack on Ukraine was simply impossible…

It is clear in any case that the interests of a NATO driven on by Washington and its Eastern European affiliates do not entirely align with those defended by Brussels and the major countries of Western Europe. The conflict approach must not prevail over diplomacy; the first on its own is insufficient, it is the lever that makes the second possible. With this in mind, it is important to support the efforts of European leaders who have now taken a path which, although narrow, is the only possible way forward: continue to support Ukraine to maintain pressure on Moscow – since Putin only understands ‘hard power’ – in order to ensure, when the time comes, the conditions for a lasting peace. As is often the case, the latter will likely require inevitable and painful concessions from both sides. If this strategy is not chosen, two equally terrible scenarios are possible: the conflict will spiral out of control or sink into a quagmire, both at the cost of untold human lives and with a highly uncertain outcome…