The war in Ukraine that began on 24 February 2022 opens a new chapter in the history of the European continent and perhaps even the world. Indeed, it is the first time since 1945 that a conflict on European soil directly involves a member of the United Nations Security Council – responsible for ensuring international peace and security – and not a minor one at that. Russia ranks as the world’s second military power. Given the legitimate concern sparked by this conflict for which Vladimir Putin is clearly responsible, there are two ways to approach the situation. As a citizen who supports democracy and strongly condemns the attack and the ensuing wave of deaths and violence, and as a scientist seeking to understand it in order to better inform political action. From this perspective, two broad questions emerge: How did we get to this point? What lessons can we draw from this major crisis so far?

The End of the Cold War: the Unification of Europe, the Dissolution of the Soviet Empire

To understand the roots of the current crisis, a summary of past events and perspectives is in order. At the root of the events of 2022 are the conditions of the end of the Cold War in Europe. In certain respects, we are currently seeing the dramatic consequences of how two different histories unfolded following key events in the 1989-1991 period: that of Europe, on the one hand, and of Russia on the other.

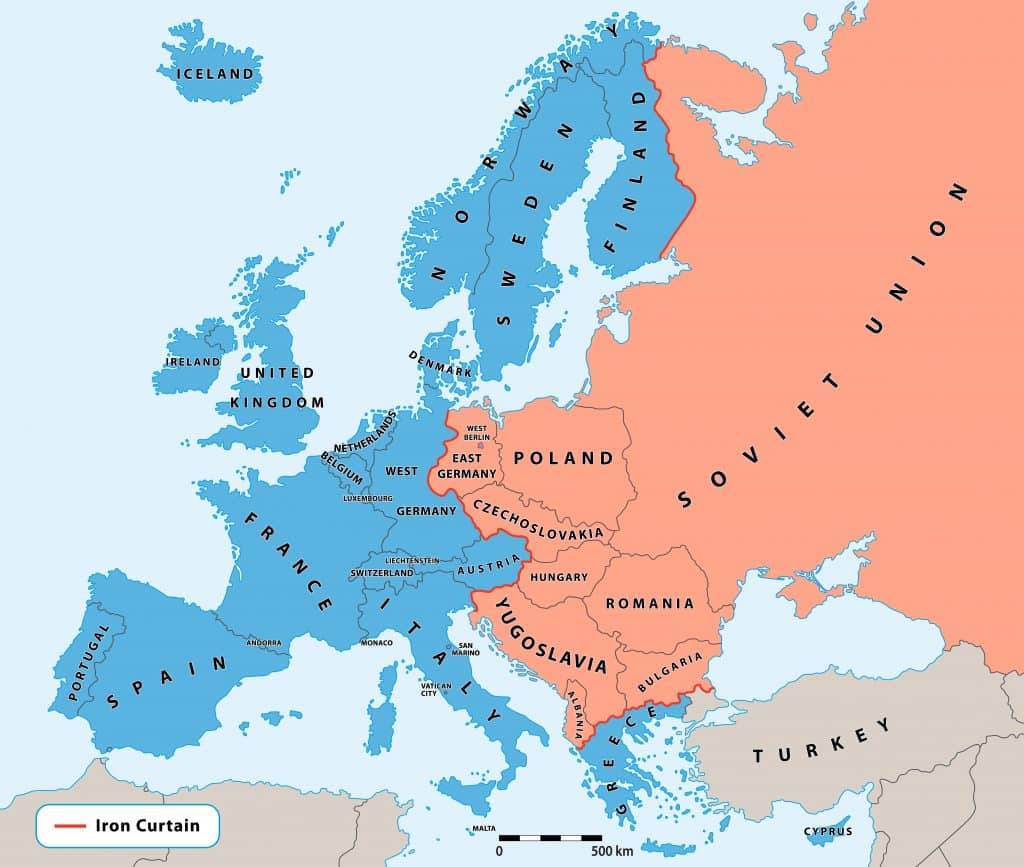

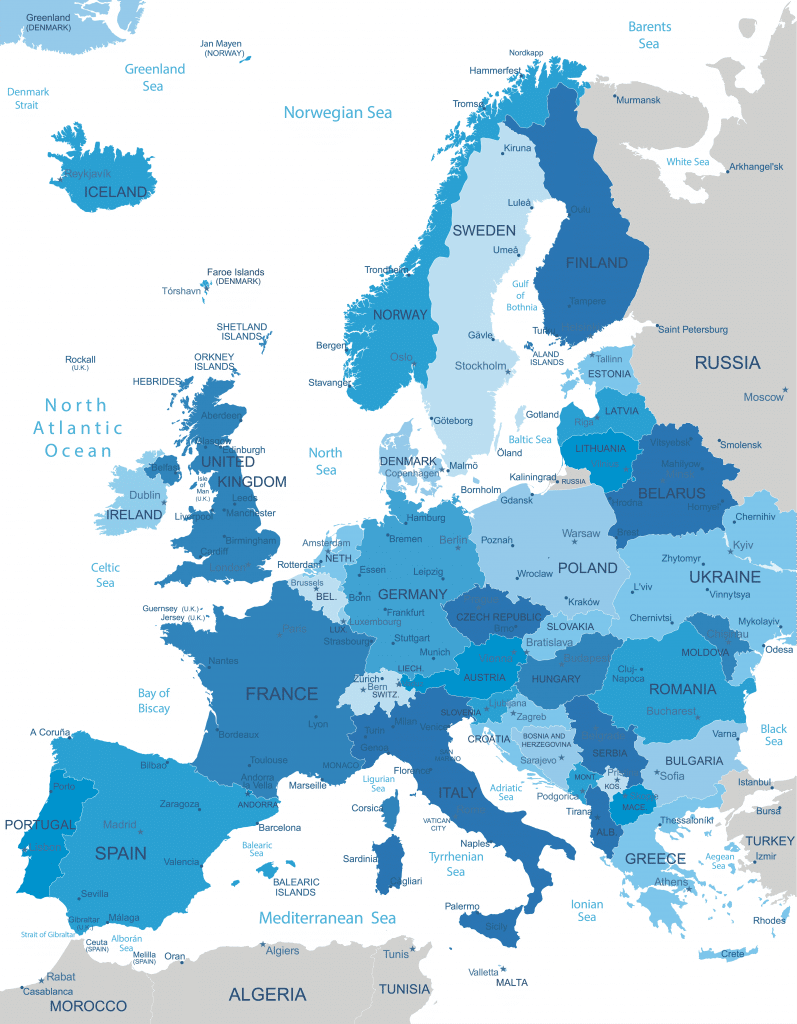

The fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989, followed by the collapse of the people’s democracies in 1989-1990, the independence of three Baltic countries in 1990, and finally the implosion of the USSR on 25 December 1991, reshaped the contours of the Europe we know today. These successive revolutions produced a striking inversion of the map of the continent: Europe, until then divided at its heart by the iron curtain, was reunified, while the USSR, hitherto bound to the people’s democracies by the Warsaw Pact, was split into some twenty independent countries.

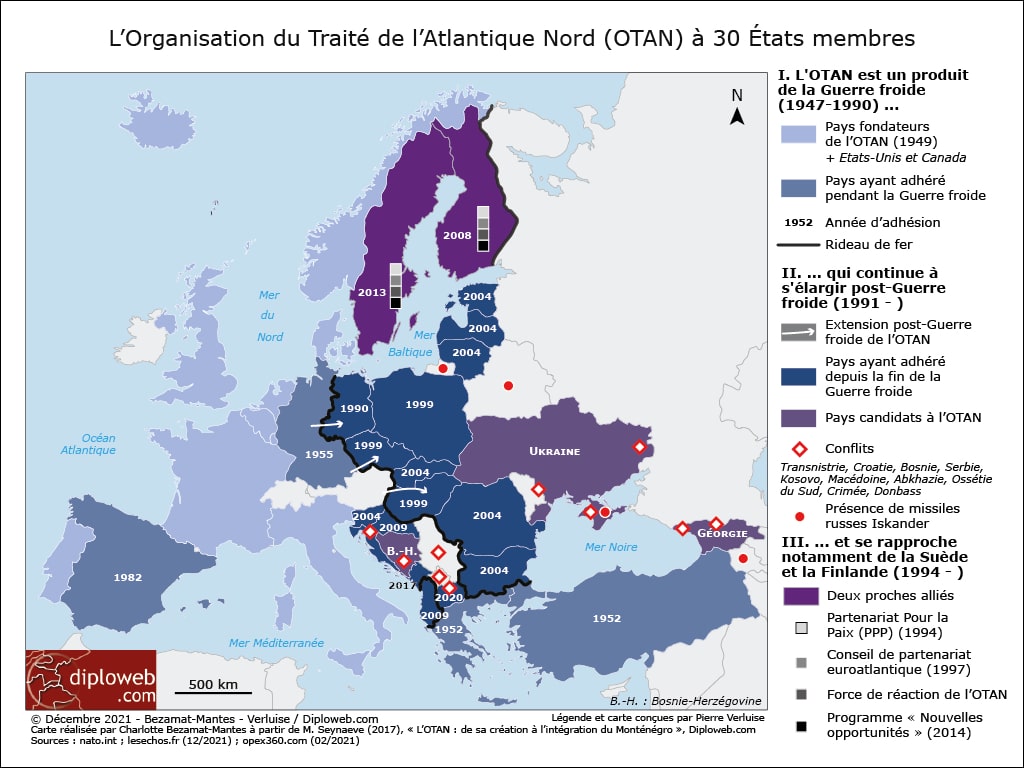

On the European side, the end of the Cold War brought the possibility of unifying the continent. The enlargements of 2004 and 2007 brought the former Eastern Europe into the fold of the European Union. Note – and this is fundamental – that these enlargements were often accompanied or preceded by NATO expansions. Indeed, to the former Soviet republics and the former people’s democracies, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) – whose role changed in the 1990s, becoming at times the armed wing of the UN, and at other times that of the United States – seemed the best guarantee against the former tutelary power of Russia, whose ambitions it feared… From the point of view of the West, the 1990s and 2000s can ultimately be summed up in three words: transition (of the former people’s democracies to a market economy and democracy), unification (of Europe within the EU following the enlargements in the 2000s), and Americanization (of the continent through NATO, whose integrated military command France rejoined in 2009 without giving up its sovereignty, all within a context of globalisation led by Washington at the time).

On the Russian side, the evolution is more a case of historical inverse symmetry. Having lost its former Baltic, eastern, Caucasian and Central Asian republics, Russia experienced a sense of decline in the 1990s which is clearly reflected in the country’s demographic makeup. In fact, in 2005 Vladimir Putin described the collapse of the Soviet Union as “the greatest geopolitical disaster of the 20th century” and said it was the “disintegration of historical Russia”. To Putin, the 1990s and 2000s were characterised by three ills: humiliation (linked to the breakup of the USSR), amputation (with the independence of former Soviet territories), and a feeling of insecurity (with the end of the protective buffer zone provided by the people’s democracies and NATO’s expansion to the very edges of the Russian world).

Restore Russian Greatness: Neo-Imperialism Motivated by Revenge

It is no secret that passions play an important role in geopolitics. According to Thucydides, three in particular motivate people and their leaders: fear, greed and pride. In Vladimir Putin’s Russia, these passions have combined into a strange mix. The head of the Kremlin is not an intellectual, but he regularly makes reference to Russian thinkers such as Ivan Ilyin, Nikolai Berdyaev, Konstantin Leontiev and Lev Gumilyov, all of whom have conservatism and neo-Slavophilism in common. The ideology he professes is certainly multiform, but it is underpinned by a conservative, religious or even mystical, revisionist (i.e. intends to revise the borders resulting from the breakup of the USSR) and expansionist nationalism, and he is intent on restoring Russia’s greatness back to what it was in the era of the Soviet Union, on account of the supposed decadence of the West. If there is a “Putin doctrine”, the idea of an empire and hostility toward the West are two of its pillars.

In fact, Vladimir Putin’s foreign policy can be interpreted as a “historical revenge” against the order that was established in Europe at the end of the Cold War, an order synonymous with “humiliation” in the eyes of Russia’s leader. It is not surprising then that the guiding principle of Putin’s policy has been the reconstitution of the former Soviet space through the use of what Joseph Nye calls ‘smart power’, or, in other words, the combination of the two forms of power, soft and hard:

- Soft power in the form of institutions such as the Eurasian Economic Union, whose ideological roots can be found in Gumilyov’s biological Eurasianism;

- Hard power in the form of threats or even military interventions. When they are not verbal, the threats take different forms, but one example worth mentioning is the fact that in 2015 Vladimir Putin asked the Russian justice system to investigate the legality of the Baltic states’ independence. For Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia, three countries home to Russian-speaking communities, this procedure is tantamount to threatening their borders. Particularly considering that in 2008 Putin had supported the separatism of two Georgian provinces, Abkhazia and South Ossetia, and had landed troops there, fracturing the territorial unity of the former Soviet republic. In 2014, he supported the Ukrainian separatist forces in Donbas and seized the opportunity to annex Crimea. Since then, Moscow has replicated the Georgian model by supporting the two separatist republics of Donetsk and Luhansk as well as the independentist forces in Donbas. A way, as was the case in Georgia, to attack the territorial integrity of a state in order to render it more vulnerable and ultimately take at least control of it.

This brings us to Ukraine. If this country holds a central place in Europe today, it is because it has been the meeting point of Russian and Western interests since the end of the Cold War. For Russia, it has become the keystone of its neo-imperial ambitions; for the West, the keystone of an expansion to the East. For the European Union, Ukraine could also be an additional link in the construction of an entity with strictly continental boundaries now that the United Kingdom is no longer a member state. While Ukraine has an abundance of natural resources, we will not be discussing these, as in our view they are not the primary motivation for the Russian intervention. Let us then examine the representations and power games of the protagonists in the conflict.

Ukraine – One Country, Three Aims: Contain, Open Up, Grow

From the perspective of Moscow, first of all, Ukraine holds a special place, both in the national imagination and due to its geostrategic location. Indeed, the country that is historically the cradle of Russia (a factual reality which does not mean that Ukrainians are Russians) is now considered by Russia’s intelligentsia and leaders to be part of “the near abroad”, a geopolitical concept forged in Russia after the Cold War to describe the now-independent, former Soviet provinces still considered by Moscow to be an integral part of the Russian civilisational space. In fact, a document written in July 2021 by the Russian president himself details his vision of Ukraine. In this essay entitled “On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians”, Vladimir Putin criticised a recent Ukrainian law that does not recognise Russians as indigenous people of Ukraine, going so far as to compare it to Nazi legislation. At the same time, he accused President Zelensky, a man of “Jewish nationality”, of being unable to determine who the real Ukrainians are… The Russian president repeated the old refrain that “Russians and Ukrainians are one people” to justify the fact that the “cradle of Russia” had to be reunified with the motherland it had left in 1991.

To these ideological arguments can be added a major geostrategic element: to achieve an imperial recomposition, or at the very least create a protective buffer zone, Vladimir Putin has five bordering countries before him – Belarus, Latvia, Estonia, Lithuania and Ukraine. The first has become a quasi-protectorate. As for the three Baltic states, they are members of the EU and NATO, meaning that a direct conflict with these would drag Russia into a confrontation with the West. As long as Ukraine is not a member of these associations, it is an easier prey to overpower. That is why as early as 2014, Vladimir Putin, with a long-term vision, set in motion a strategy to destabilise Ukraine with the Donbas War, providing support to the separatist forces and accusing Kyiv of crimes against the people in the east of the country. In fact, in his speech delivered on 24 February, the Russian president justified the invasion of Ukraine by saying it was a fight against “the genocide against the millions of people living there who rely only on Russia”, genocide committed, according to him, by extreme nationalists he described as “neo-Nazis”. Underlying these wild justifications is Moscow’s desire to annex Ukraine, as was clearly established by the great historian Timothy Snyder. On 28 February this year, he revealed certain Russian documents which the propaganda media had prepared in anticipation of a crushing victory over Kyiv, establishing that “the goals of the invasion described here [in these documents] are destruction of the Ukrainian government, control of all Ukrainian territory, the end of Ukrainian sovereignty, and a solution to the ‘Ukrainian question’”. It is clear that, from a Russian point of view, an invasion of Ukraine through Belarus and Donbas was becoming urgent, as the country was developing stronger ties with the West.

Since the 2000s, Ukraine has been caught in a tug-of-war between Russia and the European Union. Romano Prodi’s speech at the Yalta Summit in 2003, in which he expressed his wish to one day see Ukraine join the EU, followed by the signature in 2009 of the Eastern Partnership with Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia and Moldova, were too much for the Kremlin. In 2013, the latter pressured the then Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych to reject an association agreement with the EU deemed to be too big a commitment. This rejection sparked the pro-European protests on Kyiv’s Independence Square (Euromaidan) and, along with them, the February 2014 revolution, Yanukovych’s departure and… the start of the Donbas War. In this context, the annexation of Crimea by Russia should be understood as a reaction to what the Kremlin, but also the Russian population (since 84% of Russians supported the annexation), saw as Kyiv developing too close ties with Europe. In fact, in 2009, certain intellectuals close to Putin had declared, “It cannot be excluded that a battle for Crimea and Eastern Ukraine awaits us”. It is easy to see just how much the hypothetical expansion of the EU to Ukraine, which according to Putin is destined to become Russian once again, might have been perceived as a threat by the Kremlin…

The Russian feeling of containment also stems from the fact that NATO is progressing toward Ukraine. It should be noted that dialogue between Ukraine and NATO began in 1991 when Ukraine became a member of the North Atlantic Cooperation Council (NACC). The rapprochement accelerated after the Donbas War: in 2017, Ukraine’s parliament passed a bill stipulating that NATO membership was the country’s “strategic foreign policy objective”. However, since the 1990s, Russia has been steadfastly opposing NATO’s enlargement to the East. It is also worth recalling here the words of Yevgeny Primakov, a former foreign minister of Russia (1996-1998) and probably one of the most important thinkers and international relations practitioners, widely known as “Russia’s Kissinger”. Until his death in 2015, Yevgeny Primakov had been close to Putin and highly influential. He shifted Russia’s foreign policy away from support to the United States, instead giving primacy to national interests. The words he wrote about NATO in the 1990s are worth rereading today; they make up the foundations of the “Primakov doctrine”, of which Vladimir Putin is a continuator.

“For the transition to a new world order, the following two conditions are necessary.

Yevgeny Primakov – English translation based on a French translation quoted by Gilles Gressani, “La doctrine Primakov”, Le Grand Continent.

First. The divisions of old must not be renewed with new subjects. In my view, this means opposing the expansion of NATO in the countries that once belonged to the “Warsaw Pact” as well as the attempts to make NATO the principle of the new world system. This is what NATO’s bloody campaign in Yugoslavia clearly shows. This campaign was launched without the approval of the United Nations Security Council, was conducted outside the borders of member states, and had nothing to do with guaranteeing the security of NATO member countries.“

The Russians see NATO as an American geopolitical tool whose goal is to contain Moscow’s power within its national borders. This view overlooks the fact that the NATO enlargements to countries formerly in the Eastern Bloc were conducted at the request of those states, with no orders coming from Washington. Nevertheless, in 2014, to justify the annexation of Ukraine, Putin cited an unacceptable, “containment of Russia”.

“The infamous policy of containment, led in the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries, continues today. […] But there is a limit to everything. And with Ukraine, our Western partners have crossed the line, playing the bear and acting irresponsibly and unprofessionally.”

Vladimir Putin Speech, 18 March 2014

One thing is striking, in any case: as early as the 1990s, the keenest observers had underscored that Moscow would never accept the loss of Ukraine. In 1997, before Vladimir Putin came into power, before the Georgia crisis, in his book The Grand Chessboard, Zbigniew Brzezinski had written: “The independence of Ukraine changes the very nature of the Russian state. […] Without Ukraine, Russia ceases to be an empire. Russia without Ukraine can still strive for imperial status, but it would then become a predominantly Asian imperial state, more likely to be drawn into debilitating conflicts with aroused Central Asians […] However, if Moscow regains control over Ukraine, with its fifty-two million people and major resources as well as its access to the Black Sea, Russia automatically again regains the wherewithal to become a powerful imperial state, spanning Europe and Asia.” A prophetic vision if ever there was one…

NATO expansion and enlargement of the EU to the East, neo-imperial ambitions on the Russian side: two trajectories that collided in February 2022. The first is primarily motivated by a liberal approach – the right of peoples to decide their own future and to join whatever political organisations they like –, the second by a deterministic approach that would have Great Russia absorb White Russia (Belarus) and Little Russia (Ukraine) in some form or another. In some respects, the situation is reminiscent of the debate that divided Renan and Mommsen in the 19th century over the annexation of Alsace-Moselle.

These two trajectories are dictated by the pursuit of three very different aims: those of the United States are primarily strategic (“contain”), those of Europe are chiefly democratic (“open up”), and finally those of Russia are neo-imperial (“grow”). While that of the Union is idealistic, in the sense of the international relations schools of thought, those of Washington and Moscow are realistic. Perhaps that is why, regardless of what it may say, the Union plays second fiddle in this crisis. This configuration is also reminiscent of a long-standing geopolitical debate: the one opposing sea powers – including the United States – and continental powers – including Russia which, according to MacKinder is the “pivot” of the Heartland, the continental heart of Eurasia. It is fair to say that the years 1989 to 1991 did not spell the end of the story, but instead its return with, in the bargain, almost banal geopolitical tensions which the bipolarisation of the Cold War had put on hold…

What Are the Lessons?

At this stage of the conflict, it would be premature or even risky to venture a prediction as to what will happen: Will Putin win the war? Will he, on the contrary, lose Russia? Might this war be “the beginning of the end” for him? Over the past few days, the most serious magazines, such as Foreign Affairs, have been outdoing one another with contradictory articles about the war and its possible outcomes.

To (temporarily) conclude our remarks on this topic, we feel it is more realistic to consider the lessons we can already draw from the beginning of the conflict. There are several:

- This war confirms the new nature of forms of conflict. Before starting the war now being waged, the Kremlin, over a period of eight years, developed a “hybrid war” in East Ukraine. Thomas Gomart describes this type of warfare as a combination of “strategic intimidation by states with weapons of mass destruction, joint operations also involving special units and mercenaries, and large-scale disinformation manoeuvres”. Certainly, in just a few days we have gone from a limited war to a total war, but this does amount to saying that Ukraine had been engaged in a sustained conflict since 2014. While the 20th century saw confusion between civilian and military losses, the 21st century could see the line between war and peace become increasingly blurred…

- This war illustrates an intrinsic difficulty in Vladimir’s Putin’s strategy: it is tricky to ask the Russian army to bomb, kill, invade Ukraine… when the latter is home, in his own terms, to “the Russian people”. In other words, the Kremlin can hardly restore the national pride of its people by provoking a civil war. And what about a country reintegrating a motherland after having been invaded, bombarded and destroyed? One can always argue that there are precedents in Russian history – such as the crushing of the East German uprising in 1953, or of the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, both “brother” countries – and that Putin does not mind annexing a gutted territory.

- This war illustrates the difficulty in pursuing a regional strategy in a situation of complex interdependence. Indeed, Russia was expecting a quick victory, a classic example of military hubris (the Americans hoped to vanquish Islamic terrorism in 2001 by attacking Afghanistan, and pacify the Greater Middle East by toppling Saddam Hussein or Muammar Gaddafi…). The unexpected Ukrainian resistance has made things difficult for a Russian army unprepared for a lasting conflict and showing logistical weaknesses on the ground. The continuing conflict has prompted a strong and growing wave of condemnation by the international community: 11 of the 15 countries on the UN Security Council have deplored the invasion and the UN General Assembly overwhelmingly voted in favour of a resolution calling for the withdrawal of Russian forces from Ukraine. Add to this the fact that the Russian offensive has led to a marked polarisation of Europeans: Berlin, which is often magnanimous toward Moscow, quickly joined the rest of the Western camp, halting the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline project (at least temporarily…). The European Union has deployed an unprecedented arsenal of sanctions against Russia, banning the country from SWIFT, freezing the assets of Russian billionaires in Europe, and taking the decision to supply weapons to Ukraine… The Russian president’s tactic might bring him a military victory, but his strategy could be a losing one in the medium and long term given the extent to which the world powers are coalescing against his violence. This is a wonderful illustration of the “balance of threat” theory developed by Stephen Walt.

- This war calls into question the strength and stability of the Sino-Russian relationship. Many have wondered whether the invasion of Ukraine could push Beijing to invade Taiwan. But, for the time being, note that China abstained from condemning Moscow instead of joining Russia’s veto during the UN Security Council meeting. The China-Russia axis had grown spectacularly stronger over the last several years, with a joint statement issued by Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin ahead of the Beijing Olympics. But, if the conflict were to last, to what extent might Moscow become a troublesome ally for Beijing?

In any case, one thing is certain: the war in Ukraine marks a major turning point in global geopolitical relations. How it plays out could determine new geopolitical fault lines for the coming years. It is now up to us to rise to this crisis, not to abandon the Ukrainians to their fate and, at the same time, to avoid the deadly chain of events that Europe already experienced twice in the 20th century…