As Adam Smith wrote more than 250 years ago, “a lack of beneficence will make a society uncomfortable, but the prevalence of injustice will utterly destroy it.”

In a democratic country, citizens are free to express their opinions and politicians are accountable to the electorate. Logically, our businesses should reflect what these democratic societies claim to be and do, in particular by operating a governance model characterised by responsibility towards their stakeholders. Yet, our study shows that the degree of importance (or utility) in decision-making processes is unbalanced among stakeholders.

Does corporate social responsibility lead to democracy within businesses?

The concept of corporate social responsibility (CSR) provides that businesses should benefit their communities and operate sustainably – financially, socially and economically. This generally includes initiatives in spheres such as the environment, education, public health, civil and human rights and economic development. Research by business ethicists and management academics into the merits of democratising corporate governance is ongoing. Businesses and civil society are considered to play an active role in a democratic system. CSR should protect democracy and encourage societies to become more open.

But what is the situation today?

If democracy seems to be running out of steam, is this not partly because it is struggling to gain a foothold in our organisations, and in particular our businesses?

In this paper, we will endeavour to describe democracy within banks. Are banks organised in a democratic manner?

When democracy’s loss of impetus can also be seen in businesses: the example of European banks: an instructive model

We applied our model to 12 major European banks. The study covers the period 2006 to 2016.

Results

Performance by stakeholder

A lack of balance between stakeholders

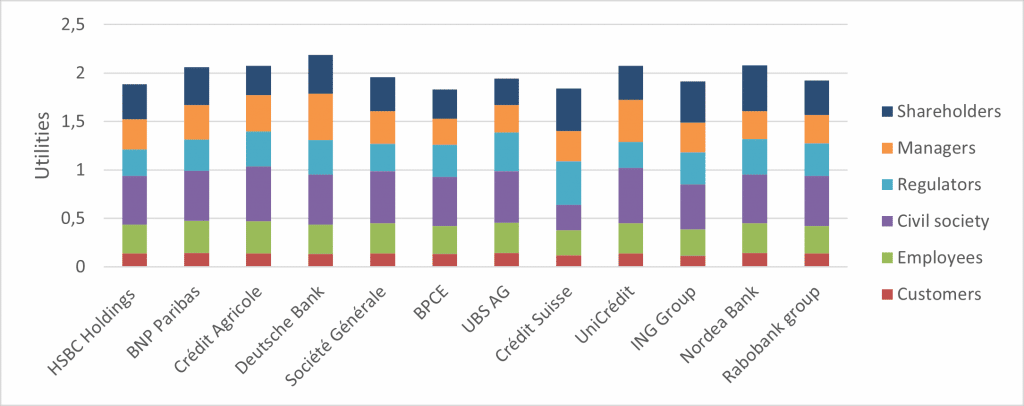

As the graph above shows, none of the banks studied achieved a balance between all the stakeholders. Our results demonstrated that most banks place a high priority on civil society (average performance of 50%) and lower priority on shareholders (average performance of 37%). This may be explained by the efforts of European banks to balance their social and economic objectives. However, their efforts are insufficient.

On the other hand, on average, looking at the remaining stakeholders, levels of utility for customers and employees are lowest. According to Chakrabarty (2004), bank charges and interest rates determine customers’ overall satisfaction. A fall in customer satisfaction was found to coincide with an increase in commissions and interest on loans. This may explain the low score from customers. Several European banks are trying to cut costs by reducing staff numbers, permanent contracts and salaries, which could explain the low score from employees. Conversely, post-crisis the performance of regulators has edged up slightly, probably due to an increased awareness of the role they play. It is clear that the performance of managers varies considerably from one year to the next for the majority of banks studied. This is probably due to the enormous variations in remuneration, and in particular the bonuses paid to managers. Managers’ compensation is usually a function of the degree to which pre-set performance objectives are met.

Business democracy has yet to be built

The results show an imbalance between the utilities for the various stakeholders. There is therefore progress to be made to improve stakeholder satisfaction and consequently the workings of democracy by increasing the recognition of the utility of each stakeholder within the productive structure. Expanding the CSR approach appears to offer a promising means of achieving this.

Banks, whose prosperity depends on democratic institutions, should re-evaluate their strategic decisions to determine whether they are undermining these institutions in any way.

This is about not only complying with hard law, such as anti-money laundering sanctions or legislation for example, but also mapping out the future from a socially responsible perspective and with a deep-rooted focus on democracy and justice. Genuine CSR is by definition voluntary. Soft law proves particularly fruitful in ensuring it is implemented. A choice that comes from inside the business, as a function of its convictions and commitments, is generally more effective than a rigid obligation imposed by an external agent.