This article was originally published by The Conversation (in French), under a Creative Commons licence.

Declaration of interests: Laurent Ferrara is a member of the steering committee of the French Economic Association (AFSE).

With inflation close to 10% and growth slowing, the British economy is dangerously close to recession. But the recent health crisis and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine are only multipliers of economic damages already produced by Brexit. How can the UK government respond to record inflation, slowing growth, low business investment and the depreciation of the pound?

In the UK, there is no end in sight to the controversy surrounding the package of measures designed to boost the economy, as it teeters on the brink of recession, with inflation running at almost 10% on an annualised basis. On Monday 3 October, the Chancellor of the Exchequer Kwasi Kwarteng announced that the government had decided to withdraw the most controversial measure unveiled in its “fiscal event”: the abolition of the 45% additional rate of income tax applied to the highest earners.

This represented a U-turn by the government on its mini fiscal policy package, presented on 23 September amid strong criticism from the opposition. The announcement of this plan caused an unprecedented fall in the value of the pound on the markets three days later, as investors worried over soaring UK government debt. On Sunday 2 October, Prime Minister Liz Truss, whose popularity has already hit record lows after just one month in the job, admitted that communication errors had been made but maintained that a policy of tax cuts was the “right decision”.

However, there is in fact no empirical evidence to support the theory advanced to underpin the scenario initially planned by Ms Truss and Mr Kwarteng, namely that cutting taxes for the rich necessarily boosts growth.

A Lack of Coherence in the Policy Mix

Most importantly, the UK’s policy mix, defined as the combination of monetary and fiscal policies, does not appear coherent. The Bank of England (BoE), like most central banks, is currently engaged in a cycle of policy interest rate increases to fight inflation, aiming to bring it back down to its targeted level of 2%. On 21 September, two days before the fiscal measures were announced, the BoE’s Monetary Policy Committee had voted to increase the Bank Rate by 0.5 percentage points to 2.25%.

Simultaneously, it had decided to gradually reduce over a period of twelve months the stock of UK government bonds that it holds, which has also contributed to tougher financial conditions. And yet, recent academic literature agrees that such a tightening has negative macroeconomic consequences which substantially increase the risk of tipping into recession.

Outcome:

- inflation, which the BoE is trying to fight, is set to be fuelled by the government’s tax cut;

- the government’s aim of generating economic growth will be thwarted by the tighter financial conditions caused by the BoE’s actions.

In addition, rather than being self-funding, the growth plan is to be financed through borrowing. This may raise eyebrows in a context where public debt is already considered high by financial markets (99.6% of GDP in Q1 2022) following several years of negative economic shocks.

There is also a high risk that a part of this fiscal plan will leak through imports, leading to an equivalent increase in the UK trade deficit, which already stood at around £30 billion in Q2 2022 (total of goods and services). In addition, initial assessments carried out in the UK have stressed that this tax cut will clearly benefit the better-off.

The UK therefore appears to be backed into a corner, especially as its economy continues to be weighed down by the consequences of Brexit.

Investment Has Been Falling since 2016

The UK economy has been hit by four negative shocks in recent years: the global financial crisis and the recession that followed in 2008-09, the exit from the European Union (Brexit) voted for in the referendum of June 2016, the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020-21 and now the energy crisis caused by the war in Ukraine following the Russian invasion on 24 February 2022.

While three of these shocks were caused by external events and outside the country’s control, the British people inflicted the Brexit crisis on themselves when they voted to leave the EU. And this is probably the shock that has caused the most damage in economic terms, in particular by shaking domestic and international business confidence.

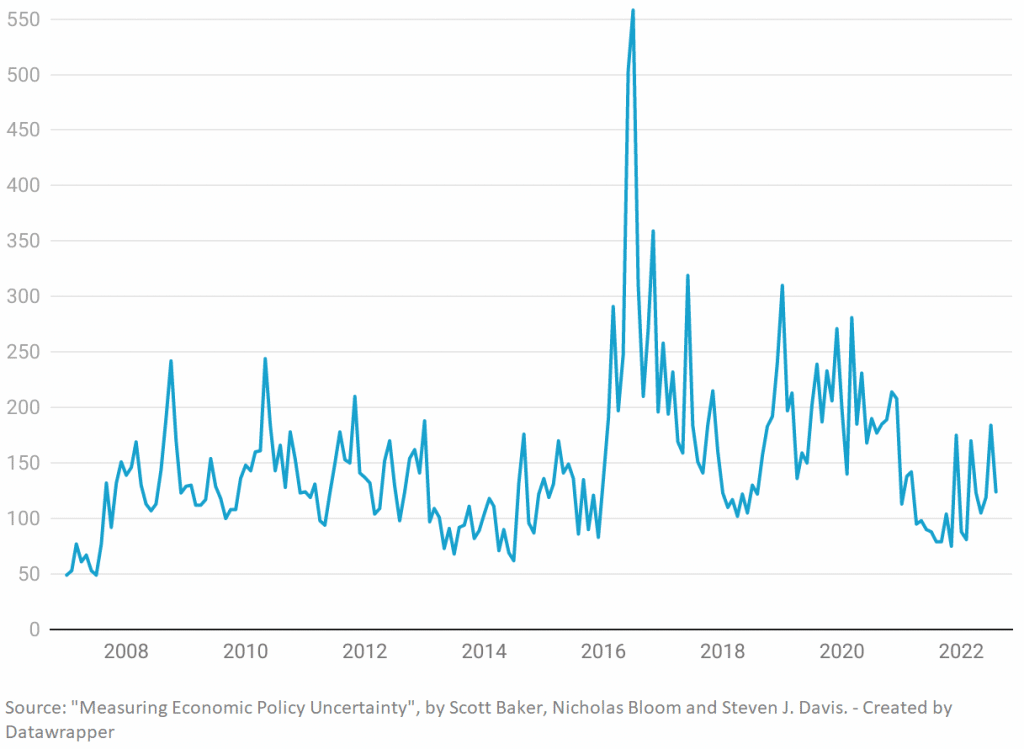

Economic policy uncertainty rapidly hit a record level after the Brexit vote, and then remained elevated after the Covid-19 pandemic hit (see graph 1).

This high economic policy uncertainty, over a relatively long period, has resulted in ongoing weakness in business investment. This is consistent with economic literature, which describes uncertainty as one of the key factors in business investment decisions, alongside expected demand and the cost of capital.

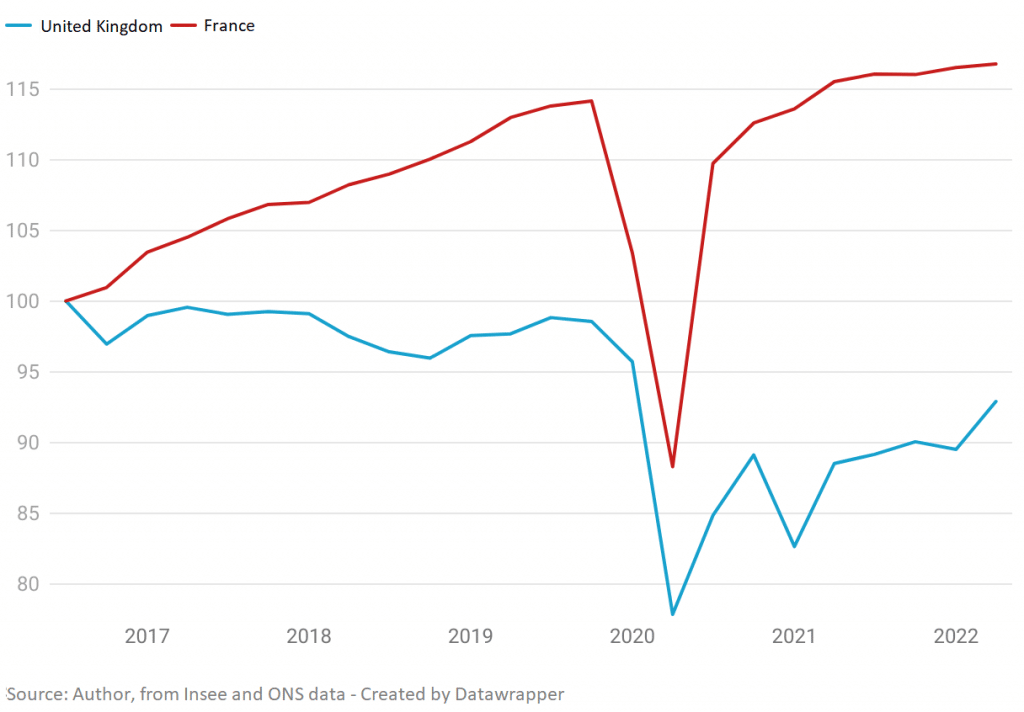

If we compare the UK with a relatively similar partner country that has not been directly affected by Brexit, such as France, we can clearly see growing divergence in levels of business investment.

During Q2 2022, UK business investment stood 7% below its level in mid-2016 (immediately after the referendum) while in France it was 17% higher (see graph 2).

Looking at the last two years, UK GDP took until 2022 Q1 to climb back above pre-Covid levels. However, initial results for 2022 Q2 suggest that GDP had fallen 0.1% compared to the previous quarter.

In this fragile macroeconomic background, the energy crisis linked to the war in Ukraine has accentuated the inflationary pressures that could already be seen during the post-Covid recovery. The Consumer Prices Index rose by 9.9% in the twelve months to August. Although a large part of this rise is due to the energy crisis, the figures put core inflation (which excludes energy, food, alcohol and tobacco) at 6.3%, suggesting considerable second-round effects.

In particular, the price of goods soared by 12.9% in a year, mainly due to a supply squeeze. This increase in inflation appears to have taken hold right across the economy: 80% of the goods and services in the consumer basket have seen inflation in excess of 4%, compared to 60% in the euro zone.*

Negative Market Reactions

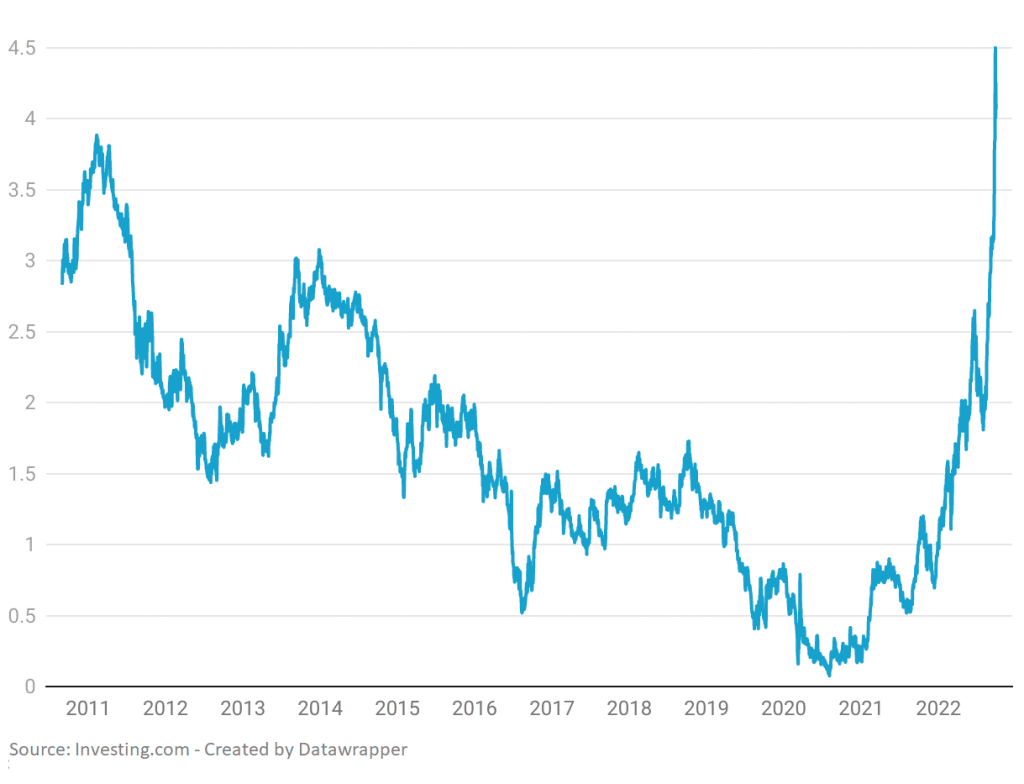

Currently, the markets are calling out the UK government’s incoherent policy mix and lack of a credible growth plan. On Tuesday 27 September, the interest rate on British government bonds climbed to 4.5%, its highest level since mid-2008 (see graph 3). This increase in long-term rates is not a positive signal from the markets. It is true that the expectation component of long-term interest rates has risen under the effect of short-term rate rise forecasts, but risk premia, both real and nominal, must undoubtedly have been re-evaluated.

On the exchange rate market, the value of sterling against the dollar has fallen by around 20% in a year, to stand at 1.07 on 27 September.

Of course, the dollar effect has played a large role in this fall, in the sense that the dollar has risen against a large number of currencies, as it always does in the face of a global crisis. However, the value of the pound, measured in terms of the nominal effective exchange rate with respect to a basket of 27 currencies, has also fallen by around 7% since the beginning of the year.

What is the effect of the weaker pound on inflation? The BoE uses an empirical rule to evaluate. A depreciation in the value of sterling is passed through to inflation in two phases, as follows: the first effect is produced by import prices (60% to 90%), and then in a second phase eventually feeds through into consumer prices, assuming that companies maintain their margins. The final effect depends on the weight of imports in consumption, estimated at around 30% in the UK. The BoE evaluates the pass-through coefficient at around 20% to 30%.

Consequently, an effective weakening of 7% would result in a price increase of between 1.5% and 2% since the beginning of the year. This is considerable and would amplify the boomerang effect of the financial markets’ assessment of how the policy mix will impact the economy.

All in all, these market developments following the announcement of the growth plan have further fuelled the tightening of financial conditions, increasing the probability of a recession over the coming months. Most growth projections for 2023 remain pessimistic: according to the OECD’s interim report published on 26 September, UK GDP is expected to stagnate in 2023 compared to 2022, raising the spectre of several quarters of negative growth.

On 26 September, the BoE published its stress-test scenario for the UK banking system. The hypothesis to be used for the test envisages simultaneous deep recessions in both the UK and global economies.

Given the consequences on financial markets of the various economic policy announcements, the BoE reversed its position on 28 September when it announced that it would immediately resume its purchases of UK government bonds, at least on a temporary basis until 14 October.

The reasoning put forward for this was a risk to the financial stability of the UK economy, for which it is also responsible. This sudden U-turn, following hard on the heels of the government’s initial growth plan announcement, is another excellent example of fiscal dominance, the principle by which monetary policy is dependent on fiscal policy. This change in monetary policy has resulted in increased financial market volatility.

To tame it, the mismatch between fiscal policy and monetary policy needs to be resolved rapidly, either through the central bank affirming its determination to fight inflation, or by clarification from the government of how it intends to fund its action plan.